When we study the functions of a gene of interest (GOI), it is common to use a combination of loss-of-function and gain-of-function assays in a study. In the era of genomics, we often use RNA-seq experiments to find out the affected genes when the level of the GOI is reduced, e.g. siRNA, shRNA & degron, or elevated e.g. over-expression. If the GOI is a transcription factor (TF), a special type of proteins that can specifically interact with DNA to regulate transcription, the natural question to ask is whether those affected genes are regulated directly by the TF. When we say “directly”, we often mean that the TF binds to the regulatory elements of a gene and regulate the transcription of that gene. This is different to the situation where the TF affects the expression of some genes which in turn change the expressions of the genes that we see in the RNA-seq experiments. How do we do that? Again, in the era of genomics, we often use ChIP-seq, which is really good at finding bona fide genome-wide binding events of a TF in an unbiased manner.

The problems

The situation was a bit different when ChIP-seq was not as common/easy/cheap as it is today. In other cases, we may only want to test if the TF binds to a few gene loci that we are interested in. To this end, we often use ChIP-PCR or ChIP-qPCR to test if a TF binds to certain places around some genes. In order to do that, we need to design primers to test the potential regions where we think the TF might bind. That was how things used to be done in early days1. There are two problems we need to solve:

- How do we know or find the potential regions where the TF might bind?

- How to design primers to validate the binding regions?

The quick answer to the first question is: we don’t! If you think about it, it actually makes sense. How do we know that without actually doing the experiments? If you already know, you don’t need to do the experiments. Very often, we see that some genes are affected by the TF via some assays such as RT-qPCRs & western blots. Then we formulate hypothesis that the TF may directly bind to the promoters of those genes, but where exactly? Well … we make our guesses. Once we have made our guess or guesses, we need to design primers to check if the TF really binds to those regions, that is, the second problem.

A not-so-short demo

Here I’m going to use a classic paper from the Medema lab that I read many times during my PhD for the demonstration.

The above paper was hereafter referred to as the Laoukili2005 paper.

FOXM1 is a forkhead transcription factor that plays an important role in regulating the progression of the cell cycle. In many cancers, it has been found that the level of FOXM1 is elevated. In this classic paper, the authors used microarray and found out that the activation of FOXM1 resulted in the elevated expressions of many G2/M genes, including CCNB1, PLK1, CENPF etc. Since FOXM1 is a transcription factor, the next question is to investigate whether FOXM1 binds to the regulatory elements of those genes to directly regulate their transcriptions. Back in 2005, ChIP-chip had not been widely adopted, and ChIP-seq had not been invented yet. How should one test those hypotheses? Or how should one detect where a transcription factor bind near a gene? Well, the answer is: mostly by educational guesses and ChIP-PCR or ChIP-qPCR to validate the guesses.

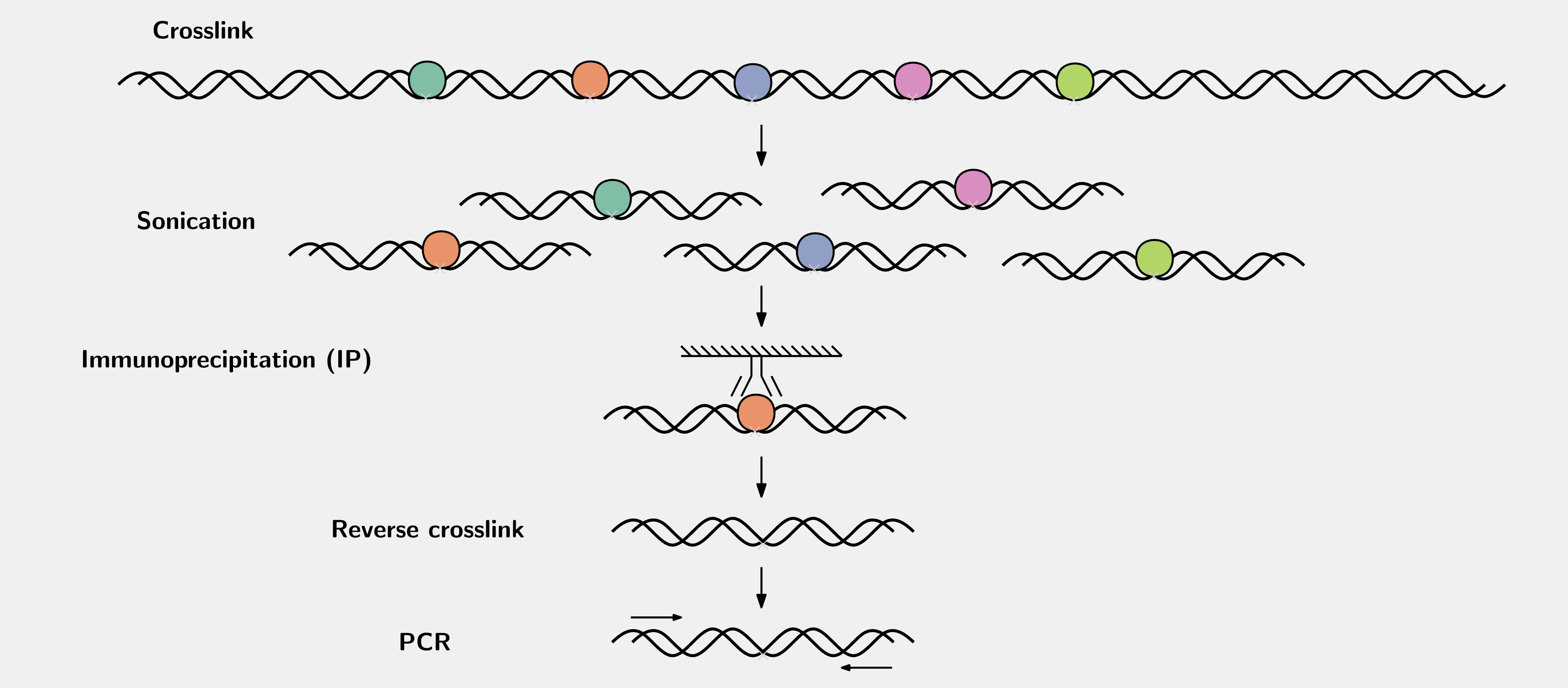

The procedures of a regular ChIP is like this:

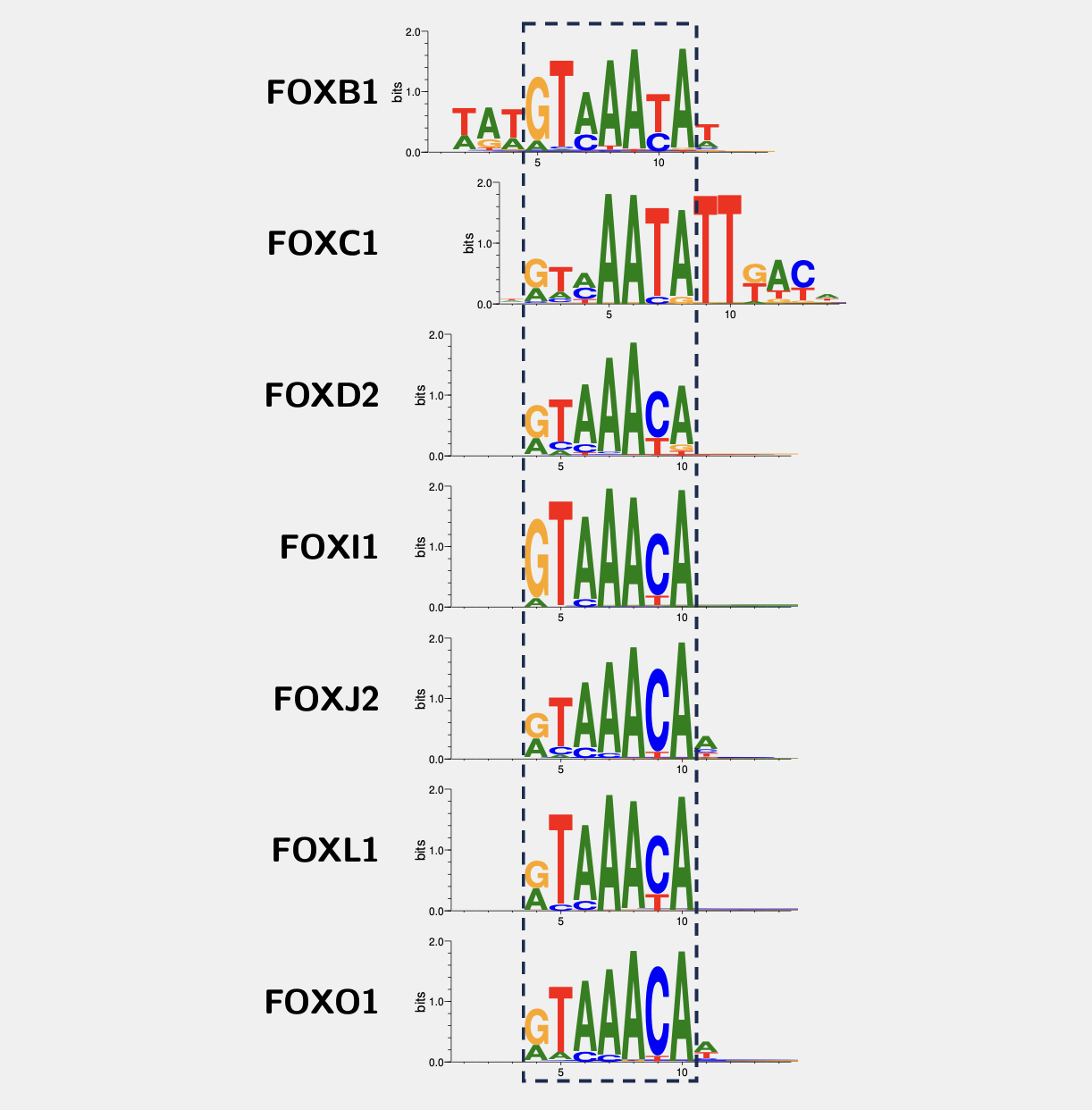

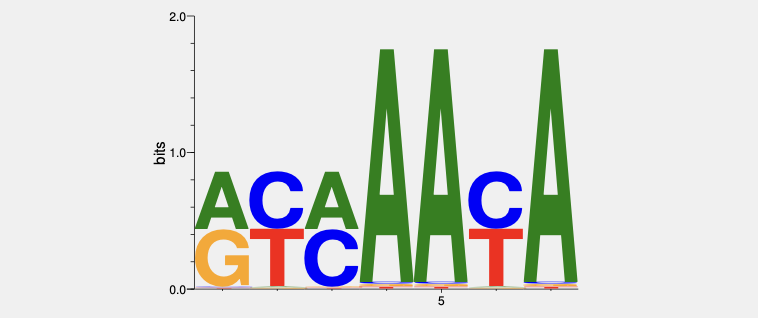

How to make the guess? In many cease, the binding sites are located in the promoter regions or nearby of the target genes2. Then considering many transcription factors interact with DNA in a sequence-specific manner, we often scan the promoter regions of the genes for a DNA motif for that factor. For example, the DNA motifs for different forkhead transcription factors based on the HT-SELEX experiments from the Jolma2013 paper are:

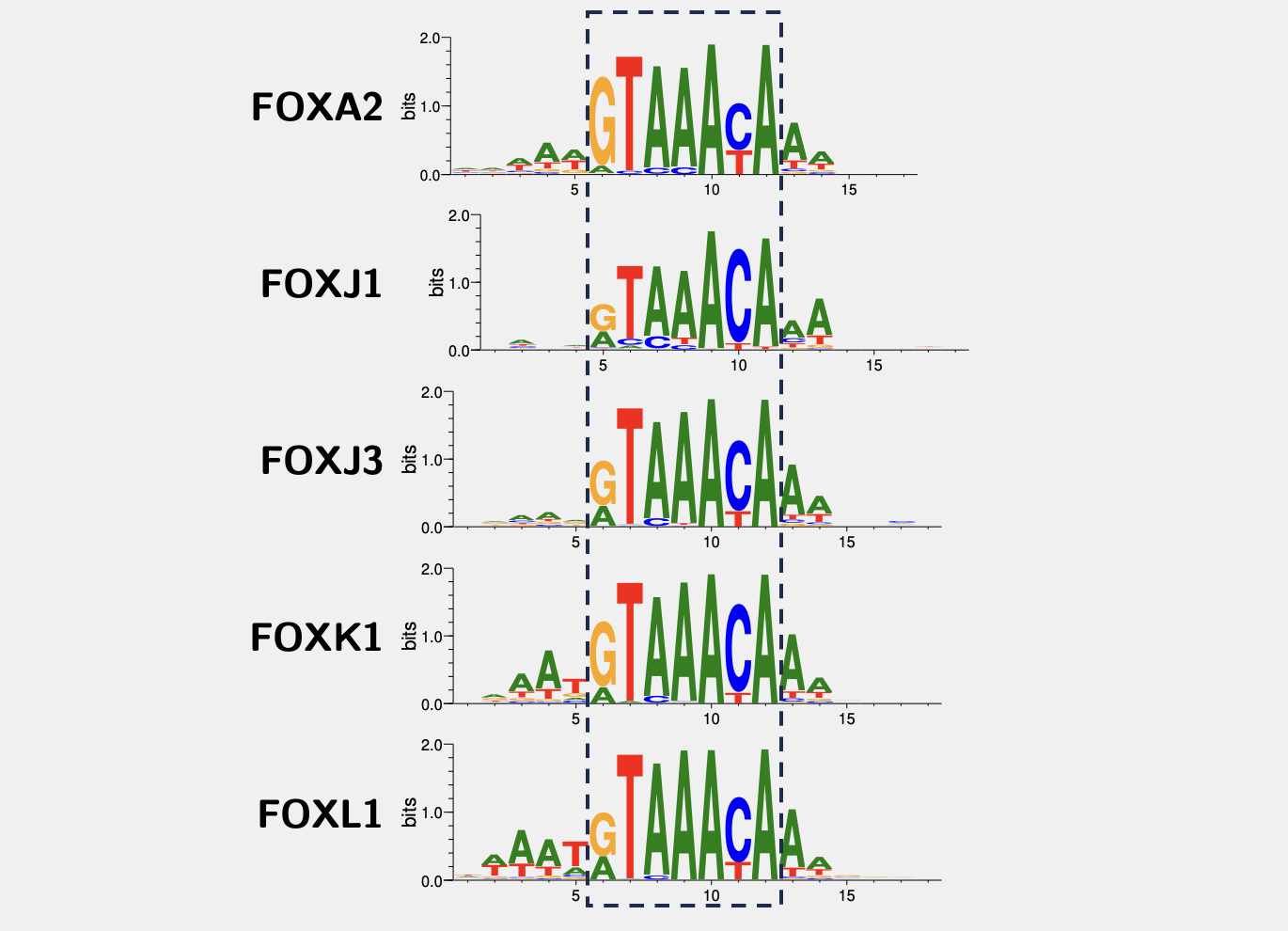

The data based on protein binding microarrays (PBM) from the Badis2009 paper suggest the motifs are:

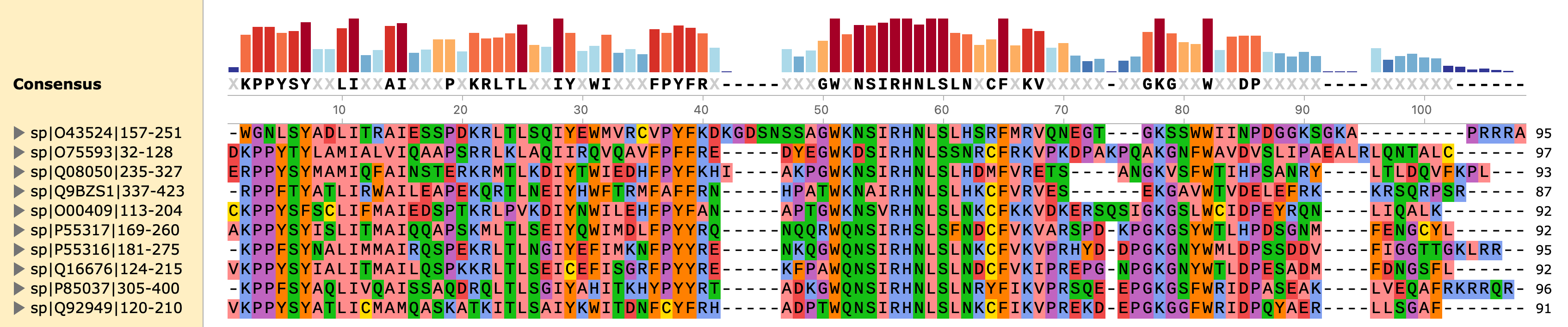

As we can see, they are kind of similar. That makes sense, because factors from the same family have conserved DNA-binding domains (DBDs). For example, all forkhead transcription factors have very similar Forkhead DBDs, shown below some examples from the UniProt database:

They all bind to the consensus 5’- GTAAACA -3’ with some minor variations at some positions that can be tolerated. Back in the days, the HT-SELEX and PBM technologies were not invented yet. The DNA motif bound by FOXM1 had been determined by traditional SELEX3 and Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA):

The above logo was recreated using seqLogo based on the data from the Costa lab (the Overdier1994 paper)4. The core consensus is something like 5'- RYMAAYA -3', with the sequences (from 5’ to 3’) ACAAACA, GTCAACA and ATAAACA having the highest affinities.

Now in the Laoukili2005 paper, the authors find the transcription factor FOXM1 regulates the expressions of Cyclin B1 (CCNB1) and CEPNF. To test if FOXM1 directly binds to the promoter regions of CCNB1 and CENPF, they designed primers to perform ChIP. They did not use qPCR but run the PCR products on agarose gels. In the paper, an ER-tagged FOXM1 was introduced. Upon 4-OH addition, the ER-tagged FOXM1 would be forced into the nucleus. The ChIP experiments were performed after 4-OH addition. The results clearly showed potential binding events of FOXM1 to the tested regions (Figure 5a and 6a in the Laoukili2005 paper). If we read through the paper, the oligo sequences used for the ChIP experiments were not included. They were available upon request.

For me, I needed those primers as my positive controls. Of course, I could email them to ask the sequences. However, back then, I thought I would not learn anything myself if I simply got the sequences from them. In addition, different labs used different PCR/qPCR systems. The ones work in one system might not work in others. Therefore, I decided to design my own for the sake of learning. That’s the whole point of PhD training.

If we check the details of the paper, we could find out that they indicated the locations of the binding sites relative to the transcriptional start sites (TSSs). Here I quote from the paper:

The cyclin B1 promoter contains a putative FoxM1 binding site 634 nucleotides upstream of the transcriptional start site. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays we could show that FoxM1 binding to this site was strongly induced upon the addition of 4-OHT to the FoxM1-ER-expressing cells (Fig. 5a), indicating that cyclin B1 is a direct target of FoxM1.

and

We could identify two potential FoxM1 binding sites in the CENP-F promoter located at 116 (BS1) and 855 nucleotides (BS2) 5′ of the defined transcriptional start. By ChIP we could show that activated FoxM1-ER rapidly binds to the CENP-F promoter region (Fig. 6a).

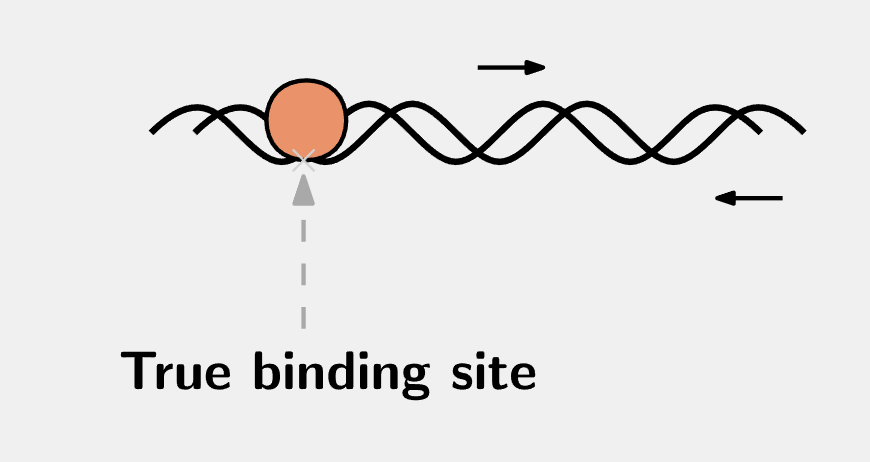

Now that we look back at those ChIP-PCR results with FOXM1 ChIP-seq data available5, we realised that they were not bona fide FOXM1 binding sites. The reasons for the positive results were likely to be amplified from the adjacent DNA regions in the same fragment, like this:

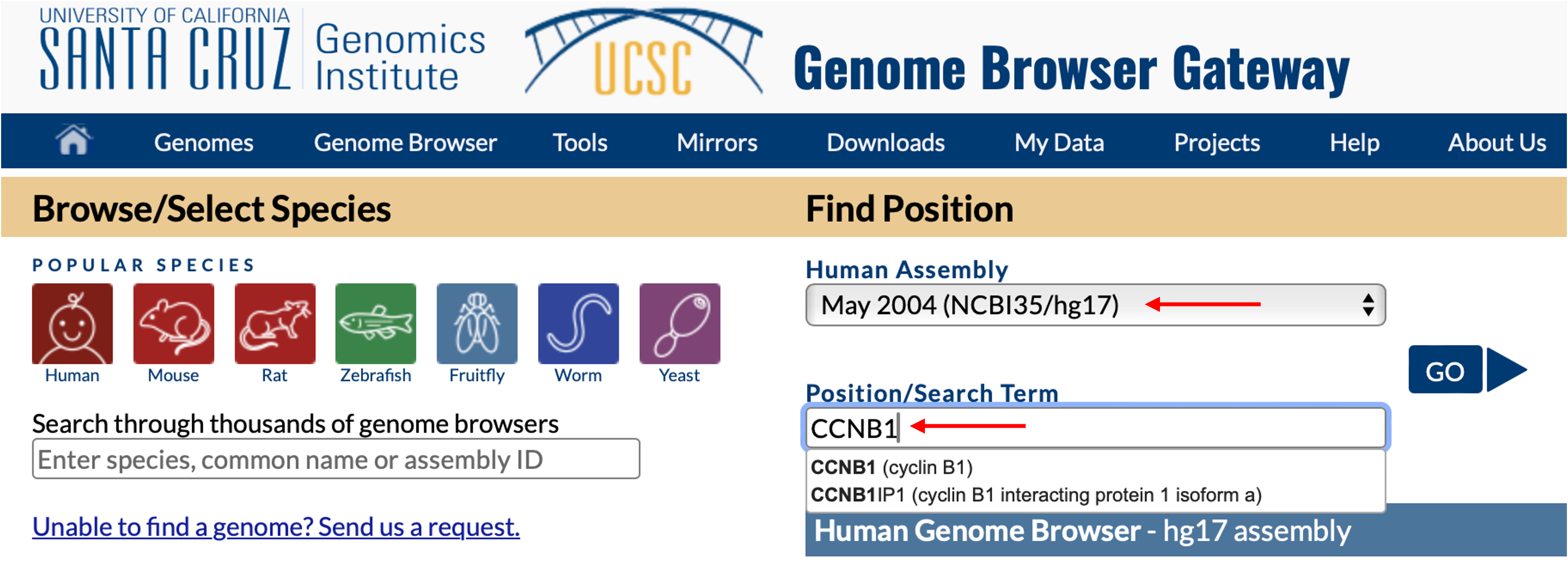

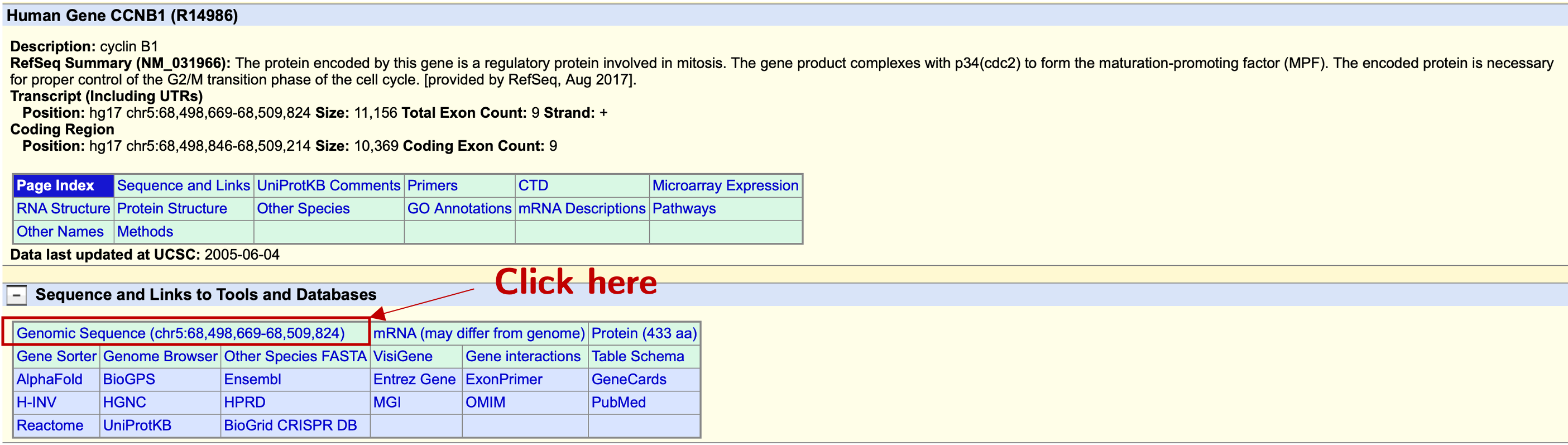

Anyway, I followed their descriptions and went to the UCSC genome browser to extract the sequence upstream of the TSSs of CCNB1 and CENPF. In this post, I’m just using CCNB1 as an example. To this end, we go to the CCNB1 locus. The build may not matter, but let’s use the May 2004 (NCBI35/hg17) build for the sake of demonstration:

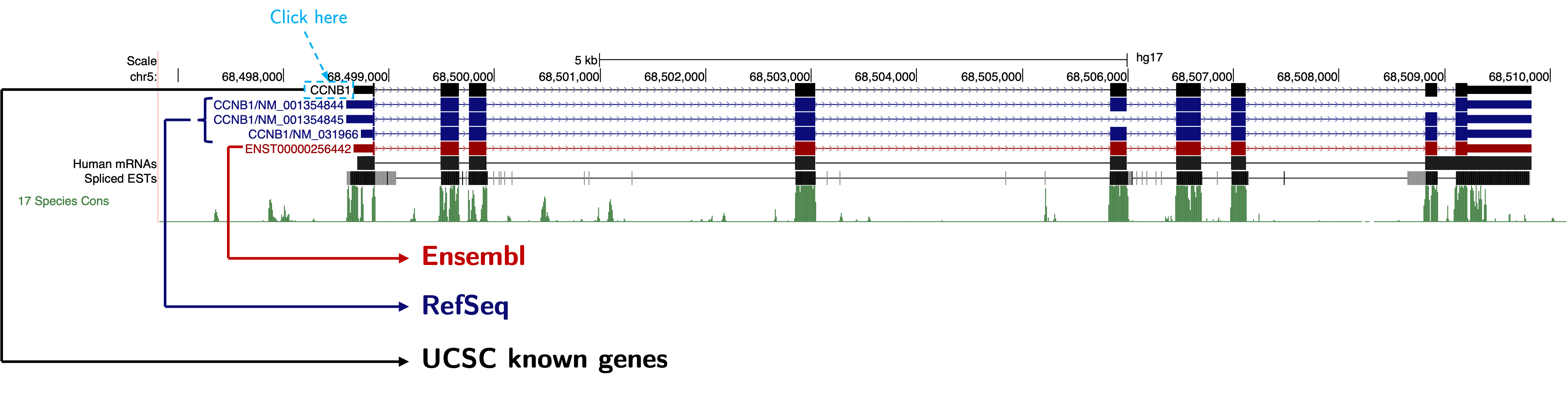

Again, there were some problems. One problem is that the exact TSS of CCNB1 is not well-defined. Different databases have different records, like this:

The black one is from UCSC known gene; the blue ones are from RefSeq; the red one is from Ensembl. Another problem is that RefSeq (the blue ones) told us CCNB1 has different isoforms with different TSSs. The differences of TSSs in different databases were not that big, so it may not actually affect the final result, since the resolution of ChIP-PCR is limited. Since UCSC known genes and Ensembl genes have the same result, let’s just use CCNB1 from UCSC known gene to demonstrate. Just click the label CCNB1 and the browser will direct us into the following page:

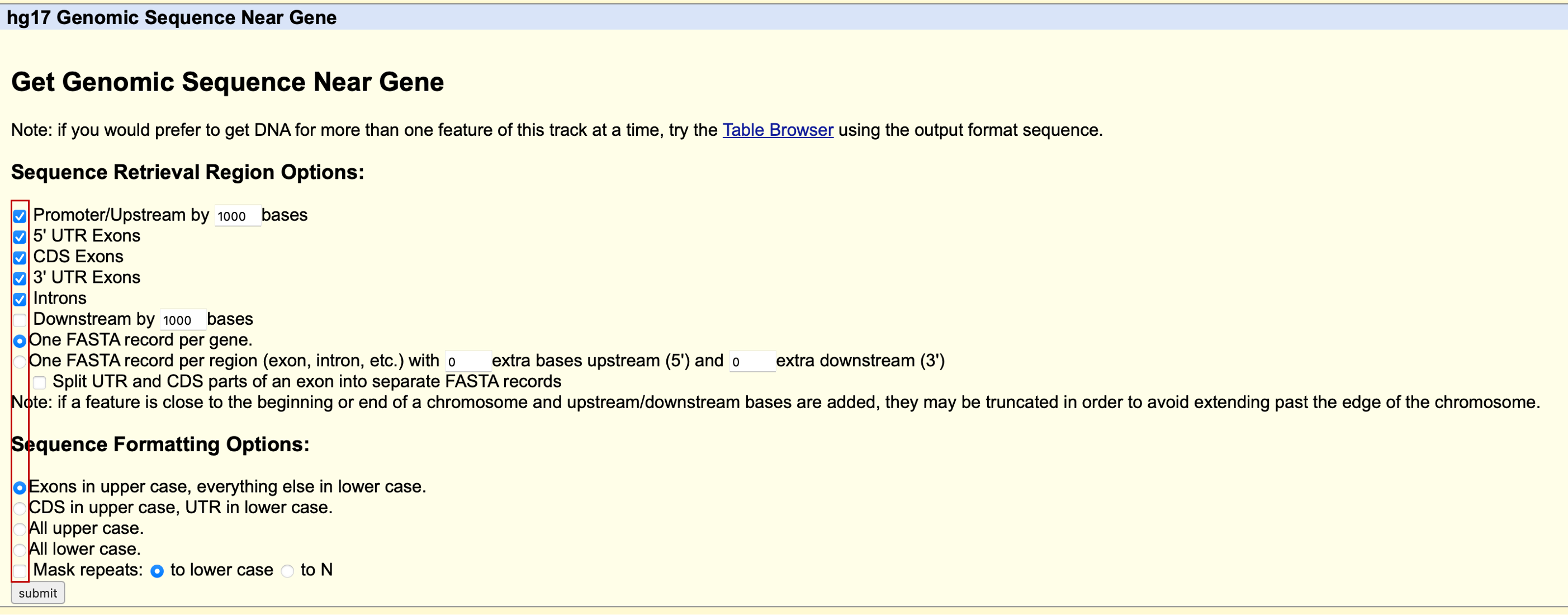

We click the Genomic Sequence field like shown above, and we are brought to this page:

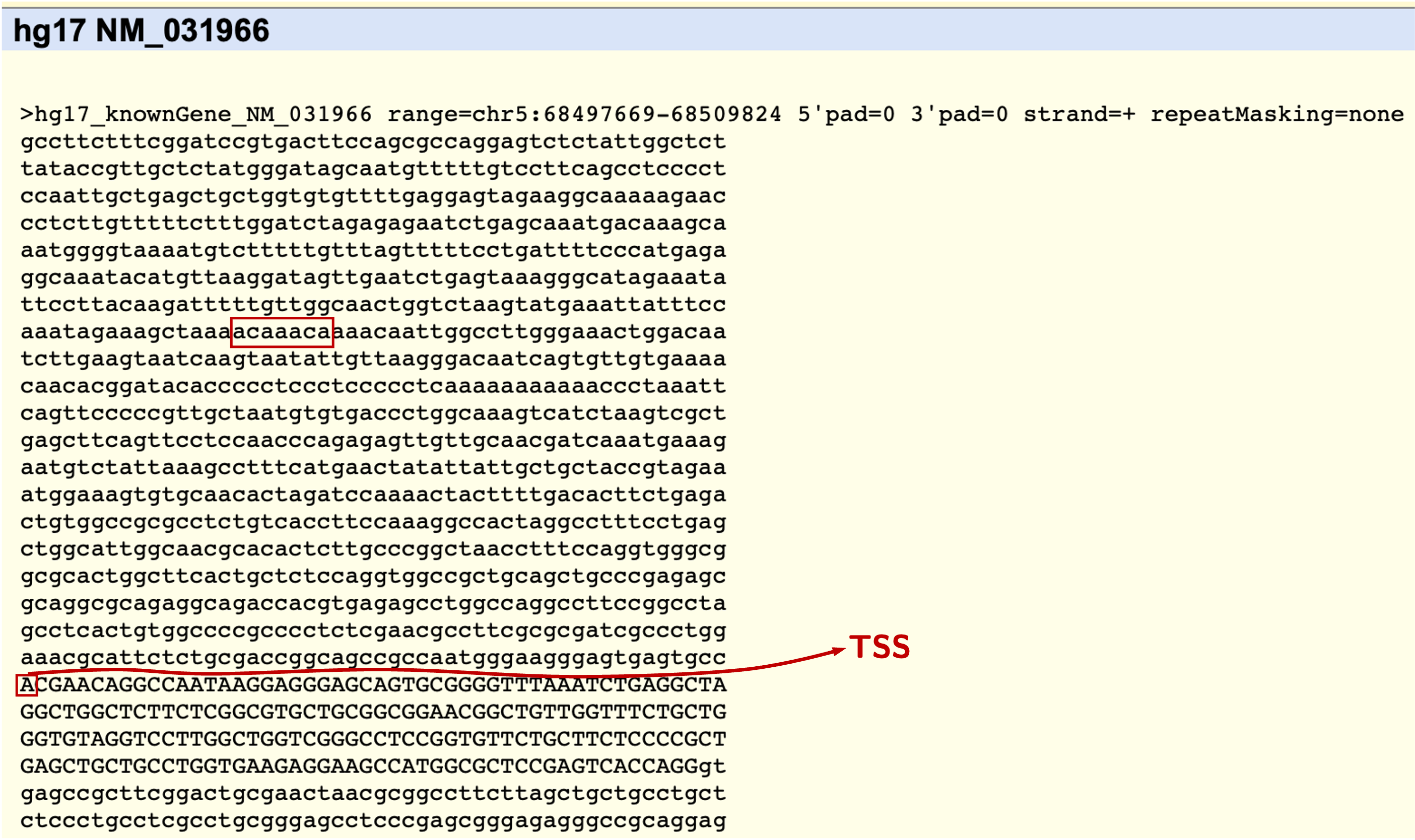

We are asked about what sequence we need, and how many bp we want at 5’ upstream. All options are self-explanatory and we just tick the options like described in the above screenshot. Click the submit button and we will end up with the following sequence in our browser, like the screenshot shown below:

The first capital letter will be the TSS. Now we go to 634 bp upstream of the TSS, and we see the sequence acaaaca which is consistent with the FOXM1 consensus. Then we are relatively confident this is probably the binding sites that the authors referred to. We only need to design primers to test this.

Primer3

How exactly do we design the primer pairs? When it comes to the primer design, Primer3 is always the go-to option for me. Back then we knew the basic principles of primer design, but we rarely did that by hand. We always used a computer program for that purpose, and the computer program follows those basic principles6. There was and there still is a web server for Primer3, which I used back in the days quite often. However, with so many web servers disappearing over the years, I now always prefer a local offline version of the programs. I only realise recently that Primer3 has been on GitHub since 2006! You can clone the repo or download a release (e.g. v2.6.1) from GitHub. Follow the instructions for installation from the manual. The installation is straightforward. You only need a C compiler and perl. Go to the src directory and compile:

cd src

make all

Once the compilation finishes without any errors, we should see some binaries under the src directory. The one we need is primer3_core. There is a text file named example in the Pimer3 directory, and the content within is:

SEQUENCE_ID=example

SEQUENCE_TEMPLATE=tattggtgaagcctcaggtagtgcagaatatgaaacttcaggatccagtgggcatgctactggtagtgctgccggccttacaggcattatggtggcaaagtcgacagagttta

PRIMER_TASK=generic

PRIMER_PICK_LEFT_PRIMER=1

PRIMER_PICK_INTERNAL_OLIGO=0

PRIMER_PICK_RIGHT_PRIMER=1

PRIMER_OPT_SIZE=20

PRIMER_MIN_SIZE=18

PRIMER_MAX_SIZE=22

PRIMER_PRODUCT_SIZE_RANGE=75-150

PRIMER_EXPLAIN_FLAG=1

=

We can start from here and use the default values for many of them. We create a new file called ccnb1 to design the primers for the CCNB1 locus, and here is the content:

SEQUENCE_ID=CCNB1

SEQUENCE_TEMPLATE=cctcttgtttttctttggatctagagagaatctgagcaaatgacaaagcaaatggggtaaaatgtctttttgtttagtttttcctgattttcccatgagaggcaaatacatgttaaggatagttgaatctgagtaaagggcatagaaatattccttacaagatttttgttggcaactggtctaagtatgaaattatttccaaatagaaagctaaaacaaacaaaacaattggccttgggaaactggacaatcttgaagtaatcaagtaatattgttaagggacaatcagtgttgtgaaaacaacacggatacaccccctccctccccctcaaaaaaaaaaaccctaaattcagttcccccgttgctaatgtgtgaccctggcaaagtcatctaagtcgctgagcttcagttcctccaacccagagagttgttgcaacgatcaaatgaaag

SEQUENCE_TARGET=215,7

PRIMER_TASK=generic

PRIMER_PICK_LEFT_PRIMER=1

PRIMER_PICK_INTERNAL_OLIGO=0

PRIMER_PICK_RIGHT_PRIMER=1

PRIMER_OPT_SIZE=20

PRIMER_MIN_SIZE=18

PRIMER_MAX_SIZE=22

PRIMER_PRODUCT_SIZE_RANGE=100-200

PRIMER_EXPLAIN_FLAG=1

=

The things that we have changed are:

SEQUENCE_ID: just put something meaningful to you and others for reference;SEQUENCE_TEMPLATE: this is the template, and we just copied the promoter sequence flanking theacaaacamotif from the CCNB1 promoter that we have got from the UCSC genome browser. I often copy roughly 200 bp up and downstream of the binding sites as the template, but I don’t think this is so important as long as the template has a decent length.SEQUENCE_TARGET: accepts two values separated by comma. The first value is the 0-based (inclusive) coordinates of the starting point of the target, and the second value is the length of the target. If we set these values, Primer3 would make sure the output primers are all flanking the target, so that the target would be amplified. Here, the putative binding siteacaaacais our target, which starts at the 215th (0-based) bp from the chosen template with a length of 7bp.PRIMER_PRODUCT_SIZE_RANGE: we normally choose 100-200 for qPCR.

Another nice thing that Primer3 can do is to scan against a mispriming library to avoid designing primers that can land on those sites. This is essentially a FASTA file with some repeat regions in the genome. You can check the Primer3 manual for a detailed explanation with guides on how to generate your own mispriming libraries. Luckily, for humans, we already have the library provided by the Primer3 authors. They are located in the Primer3Plus GitHub repo. This option is not turned on by default, but I have found that using a mispriming library increases the chance of success. Therefore, I always use it whenever we design ChIP primers.

First, we download the file:

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/primer3-org/primer3plus/master/server/mispriming_lib/humrep_and_simple.txt

which is the required FASTA file. Then we need to turn on this functionality. In the Primer3 directory, there is a subdirectory named setting_files. Within the subdirectory, we should see a file named primer3web_v3_0_0_default_settings.txt. We leave all content in that file unchanged, but modify the following line (line 12 if you use v2.6.1):

PRIMER_MISPRIMING_LIBRARY=

to

PRIMER_MISPRIMING_LIBRARY=/path/to/humrep_and_simple.txt

As you can see, we just put there the path to the humrep_and_simple.txt that we just downloaded. Now we run the following command:

src/primer3_core \

--format_output \

--p3_settings_file ./settings_files/primer3web_v3_0_0_default_settings.txt \

ccnb1

You should see a nice and clear output, just like that from the web interface:

PRIMER PICKING RESULTS FOR CCNB1

Using mispriming library ./humrep_and_simple.txt

Using 1-based sequence positions

OLIGO start len tm gc% any_th 3'_th hairpin rep seq

LEFT PRIMER 84 21 57.99 47.62 0.00 0.00 0.00 10.00 ctgattttcccatgagaggca

RIGHT PRIMER 246 20 58.65 50.00 5.01 0.00 0.00 11.00 ccagtttcccaaggccaatt

SEQUENCE SIZE: 450

INCLUDED REGION SIZE: 450

PRODUCT SIZE: 163, PAIR ANY_TH COMPL: 0.00, PAIR 3'_TH COMPL: 0.00

TARGETS (start, len)*: 215,7

1 cctcttgtttttctttggatctagagagaatctgagcaaatgacaaagcaaatggggtaa

61 aatgtctttttgtttagtttttcctgattttcccatgagaggcaaatacatgttaaggat

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

121 agttgaatctgagtaaagggcatagaaatattccttacaagatttttgttggcaactggt

181 ctaagtatgaaattatttccaaatagaaagctaaaacaaacaaaacaattggccttggga

******* <<<<<<<<<<<<<<

241 aactggacaatcttgaagtaatcaagtaatattgttaagggacaatcagtgttgtgaaaa

<<<<<<

301 caacacggatacaccccctccctccccctcaaaaaaaaaaaccctaaattcagttccccc

361 gttgctaatgtgtgaccctggcaaagtcatctaagtcgctgagcttcagttcctccaacc

421 cagagagttgttgcaacgatcaaatgaaag

KEYS (in order of precedence):

****** target

>>>>>> left primer

<<<<<< right primer

ADDITIONAL OLIGOS

start len tm gc% any_th 3'_th hairpin rep seq

1 LEFT PRIMER 89 22 57.69 40.91 0.00 0.00 0.00 12.00 tttcccatgagaggcaaataca

RIGHT PRIMER 244 21 58.59 42.86 5.01 0.00 0.00 11.00 agtttcccaaggccaattgtt

PRODUCT SIZE: 156, PAIR ANY_TH COMPL: 0.00, PAIR 3'_TH COMPL: 0.00

Statistics

con too in in not no tm tm high high high high high

sid many tar excl ok bad GC too too any_th 3'_th hair- lib poly end

ered Ns get reg reg GC% clamp low high compl compl pin sim X stab ok

Left 877 0 0 0 0 292 0 517 0 0 0 10 1 38 0 19

Right 887 0 0 0 0 155 0 404 26 0 0 0 0 51 0 251

Pair Stats:

considered 2322, unacceptable product size 2315, high mispriming library similarity 5, primer in pair overlaps a primer in a better pair 2365, ok 2

libprimer3 release 2.6.1

Note that when we used a setting file like primer3web_v3_0_0_default_settings.txt, the position index becomes 1-based. That’s why we saw an offset of our target in the above output (indicated by *). It would not affect the final results much. To change it, we could change the line PRIMER_FIRST_BASE_INDEX=1 in the setting file to PRIMER_FIRST_BASE_INDEX=0.

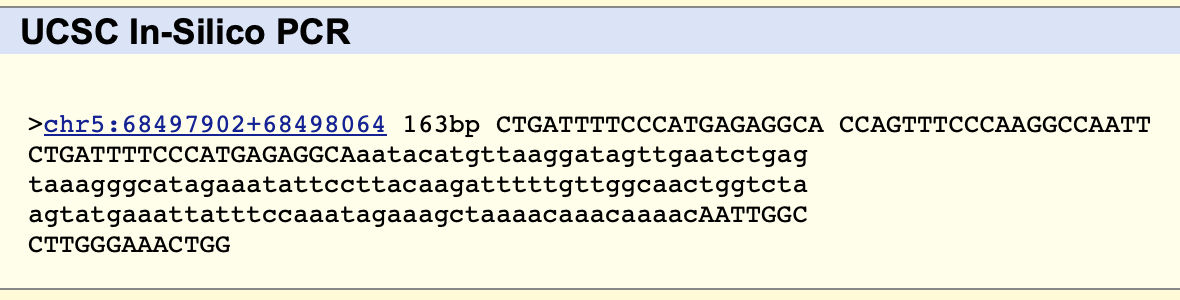

Validation

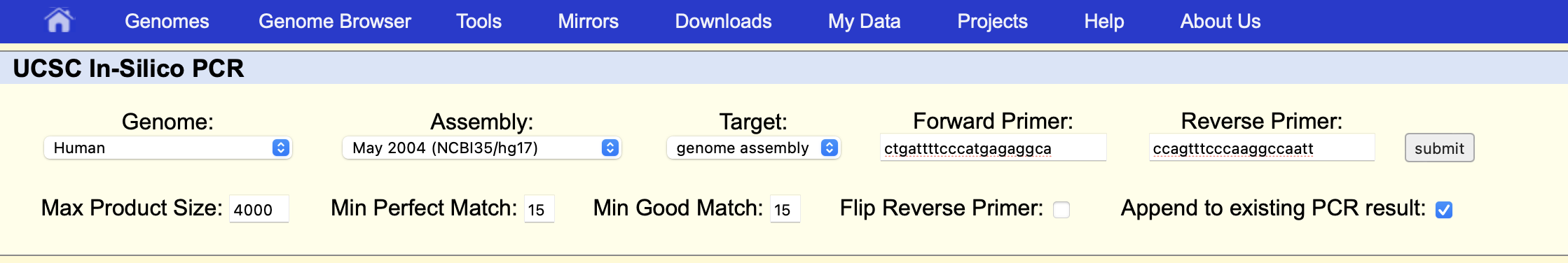

Once we get the results, we often choose the first one and do some sort of validation. To this end, we head to UCSC and use the in-silico PCR functionality under the Tools tab shown below:

Put the forward and reverse primers returned by Primer3 into the corresponding boxes like this:

Click the “submit” button and we will get:

We can see the expected product size is consistent with the Primer3 output and the genomic coordinates of the PCR product. With this, we are satisfied and can proceed to order the oligos from our favourite vendors.

One thing that we need to know is that the above procedures do not guarantee us a pair of primers that work. If the first pair turns out not working, we just order other ones from the Primer3 output and test by ourselves.

Final comments

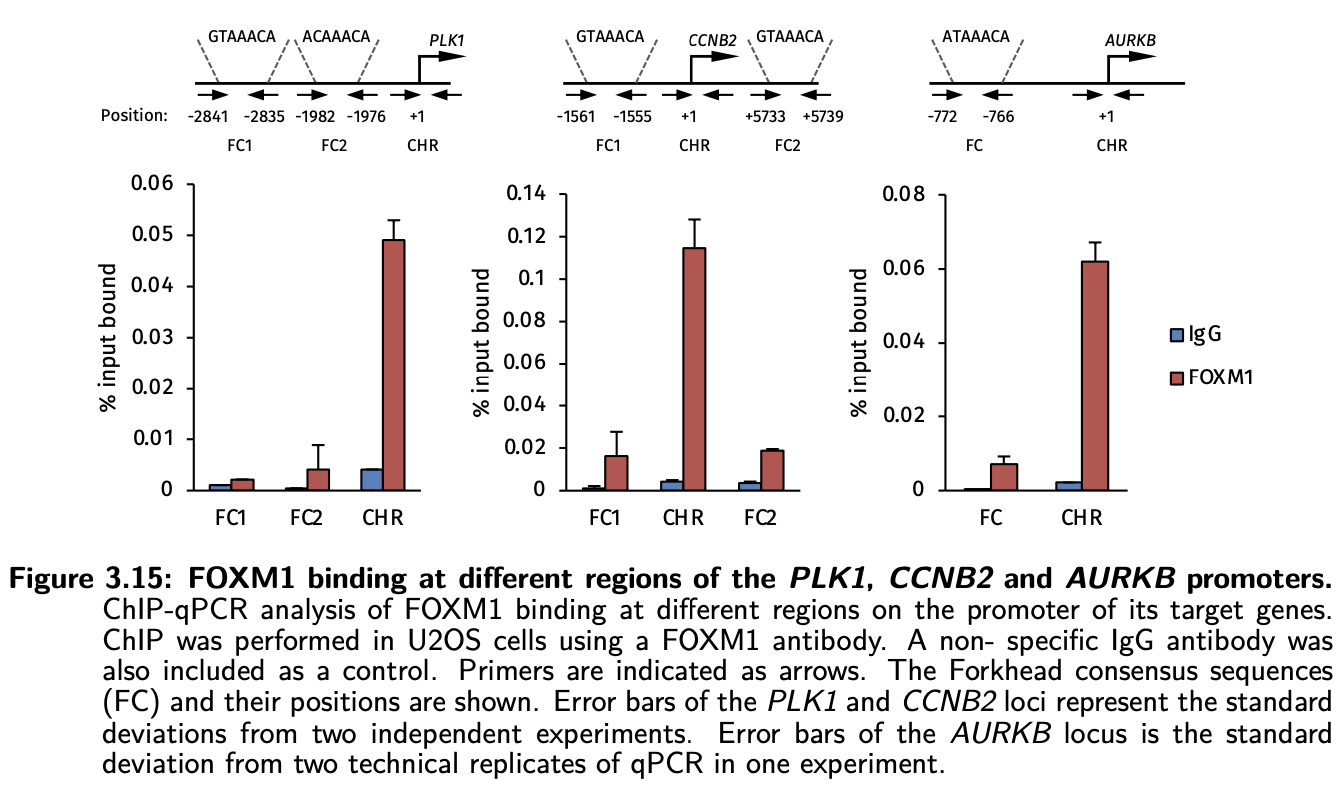

Like mentioned in the previous section, the binding site here (634 bp upstream of CCNB1 TSS) is not a true FOXM1 binding site. The actual binding site is located very close to the TSS of CCNB1 where the cell cycle homology region (CHR) is located:

In general, we often design primer pairs to scan a few regions near the TSS of a potential target genes like shown in the above picture from my PhD thesis. This gives us the best chance of finding the true binding site. Nowadays, we may just do a ChIP-seq experiment which is the best way and the gold standard of getting the genome-wide binding events of a TF.

Well, not so early I guess. In really early days, people used the Southern blot for that purpose. ↩︎

Technically, the statement is not entirely true. Most binding sites of a transcription factors are in the intronic and intergenic regions. However, the best we can to do is to scan the promoter regions. That was also the easiest and the most straightforward thing to do. ↩︎

There seems to be different names for this type of methods, such as cyclic amplification and selection of targets (CASTing), target detection assay (TDA) and selected and amplified binding site (SAAB). See this reference. ↩︎

Robert Costa made huge contributions to the biology of FOXM1 and sadly passed away in 2006. ↩︎

For example, this paper, this paper and ENCODE data. ↩︎

Not sure how people did it before such programs existed, but I guess they had to do it by hand. A good reference about primer design is Wojciech Rychlik (1993) “Selection of Primers for Polymerase Chain Reaction” in BA White, Ed., “Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 15: PCR Protocols: Current Methods and Applications”, pp 31-40, Humana Press, Totowa NJ. recommended by the authors of Primer3. ↩︎