This is the second post from a series where I use the recent PIP-seq data as an example to demonstrate the importance to use a common standard like seqspec to accompany sequencing reads submissions into public repositories.

An Initial Look

The PIP-seq method was originally put on bioRxiv on 13 June 2022. It means the method was under development way ahead of that date. The final publication in Nature Biotechnology (Clark2023) is on 06 March 2023. If we consider the time between the start of the method development and the final publication, it is not surprising to see different versions of the method in the paper. This is indeed the case which we will demonstrate.

Now we focused on figuring out the library structure and identify the meaning of each base. The method section is always a good starting point, and I copy-paste here:

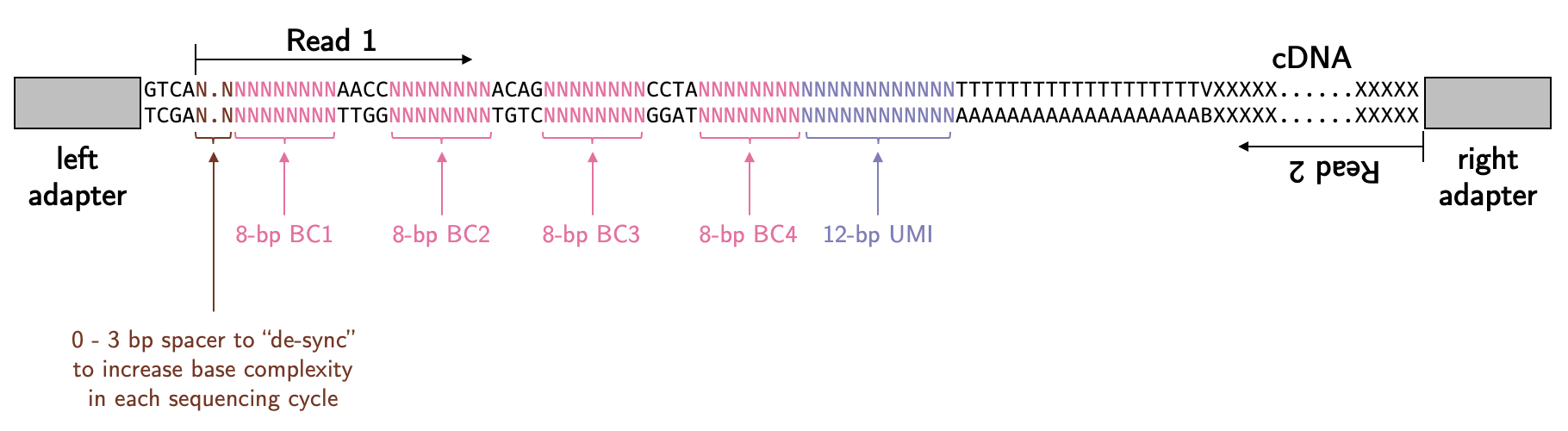

Synthesis of barcoded bead templates Prototype barcode bead fabrication proceeded according to previous reports $^{30}$. Briefly, a simple coflow microfluidic device was used to combine acrylamide premix (6% (wt/vol) acrylamide, 0.1% bis-acrylimide, 0.3% (wt/vol) ammonium persulfate, 0.1× Tris-buffered saline–EDTA (TBSET: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 137 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 1.4 mM KCl and 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100), 50 µM acrydited primer (/5Acryd/TTTTTTTAAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACGACTCCTC TTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCC ) with oil (HFE 7500, 3M Novec) containing 2% (wt/vol) surfactant (008-Fluoro-surfactant, Ran Technologies) and 0.4% (vol/vol) tetramethylethylenediamine). … … … The process was repeated to add four barcodes and a UMI with poly(T) (NNNNNNNNNNNNTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTV). Quality control steps were identical to previous reports $^{30}$.

Reference 30 (Delley2021) is a paper about how to generate barcoded beads from the same lab. If you follow the instructions, you will see it is based on combinatorial barcoding using the split-pool strategy that is similar to how inDrop generates the beads. The methods in the Clark2023 paper is not detailed enough for us to figure out the library structure. If we combined the sequences in the Clark2023 paper and the workflow in the Delley2021 paper, we might expect the library structure to be something like this:

Therefore, we would expect the read 1 should start with 0 - 3bp variable bases, followed by four sets of 8-bp barcodes with defined spacers in between and then 12-bp UMI. Is this correct? Let’s have a look.

GSE202919

Now let’s go to GSE202919, which has the data associated with the Clark2023 paper. We can simply try the first one (which turns out to be a really bad starting point if you read other posts from this series … anyway …):

GSM6106784 Fresh 2000 cell H1975 with drug treatment

which eventually points to SRR19086119, SRR19086120, SRR19086121 and SRR19086122. Get the FASTQ files for the first one:

$ fastq-dump --split-3 -A SRR19086119

Then we use grep with regular expressions to see if we could see our expected structure. We only need to have a look at the first 1 million reads to get an idea:

zcat SRR19086119_1.fastq.gz | \

sed -n '2~4 p' | \

head -1000000 | \

grep -P '^[ACGTN]{8,11}AACC[ACGTN]{8}ACAG[ACGTN]{8}CCTA[ACGTN]{20}T*'

Nothing showed up. Maybe we are being too stringent. Let’s grep the beginning part:

zcat SRR19086119_1.fastq.gz | \

sed -n '2~4 p' | \

head -1000000 | \

grep -P '^[ACGTN]{8,11}AACC[ACGTN]{8}'

Only 79 out of the 1 million reads have the match. Here are the top 5 mathes:

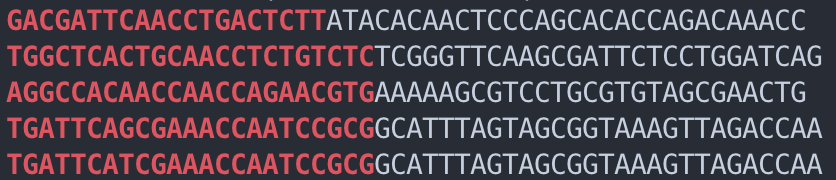

and we can see that the sequences after the matching are not what we expect. We can also try a few other patterns, such as

'[ACGTN]{8,11}AACC[ACGTN]{8}'

'AACC[ACGTN]{8}ACAG'

'[ACGTN]{8}ACAG[ACGTN]{8}CCTA'

We can try a few, but nothing makes sense. Therefore, the sequences described in the Delley2021 paper is definitely not used here.

In the Clark2023 paper, they mentioned they have a commercial company (Fluent BioSciences) that provide the product now. They have their own preprocessing and analysis program: PIPseeker$^{\textmd{TM}}$. Maybe that will help, at least it may help us make educational guesses.

Go to the page and download the software, which is just a large binary file (327 MB). Let’s run the first step of the program on SRR19086119. Note that the software is not very flexible with file names, so we have to do some extra manipulation in advance:

# create a folder to hold the original fastq files

# then create symlink with names similar to bcl2fastq

$ mkdir -p SRR19086119

$ ln -s ../SRR19086119_1.fastq.gz SRR19086119/SRR19086119_R1_001.fastq.gz

$ ln -s ../SRR19086119_2.fastq.gz SRR19086119/SRR19086119_R2_001.fastq.gz

# now your current directory looks like this

$ tree .

.

├── SRR19086119_1.fastq.gz

├── SRR19086119_2.fastq.gz

└── SRR19086119

├── SRR19086119_R1_001.fastq.gz -> ../SRR19086119_1.fastq.gz

└── SRR19086119_R2_001.fastq.gz -> ../SRR19086119_2.fastq.gz

## Check the manual and run pipseeker barcode

pipseeker barcode \

--output-path ./barcode/ \

--skip-version-check \

--threads 4 \

--random-seed 42 \

--fastq ./SRR19086119/. # note the trailing dot

Then the following error message was shown:

2023-06-03_15-44-18 Running PIPseeker v02.01.04

2023-06-03_15-44-18 Copyright (c) 2023 Fluent BioSciences. All rights reserved.

2023-06-03_15-44-19 PIPseeker is up to date

2023-06-03_15-44-20 Unable to automatically detect chemistry version. Please use --chemistry to choose from: v3, v4

Then if the chemistry version v3 or v4 were explicitly stated, very very few barcodes were detected.

After messing around with the second and the third samples of GSE202919, I gave up and decided to check the example data from the company’s website instead.

The FluentBio Example Data

The rationale is that at least the example data on the website should be compatible with the software. Let’s start with the smaller one: the NIH3T3+HEK293T species mixing experiment with the T2 kit. Extract the files and organise the directory like this and run under the first level directory:

# directory structure

fluentbio

└── fastqs

├── RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz

├── RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R2_001.fastq.gz

├── RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L002_R1_001.fastq.gz

└── RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L002_R2_001.fastq.gz

# run under fluentbio

pipseeker barcode \

--output-path ./barcode/ \

--skip-version-check \

--threads 4 \

--random-seed 42 \

--fastq ./fastqs/.

After it is finished, some new files are produced and the directory looks like this:

fluentbio

├── barcode

│ ├── barcoded_fastqs

│ │ ├── barcoded_1_R1.fastq.gz

│ │ ├── barcoded_1_R2.fastq.gz

│ │ ├── barcoded_2_R1.fastq.gz

│ │ ├── barcoded_2_R2.fastq.gz

│ │ ├── barcoded_3_R1.fastq.gz

│ │ ├── barcoded_3_R2.fastq.gz

│ │ ├── barcoded_4_R1.fastq.gz

│ │ └── barcoded_4_R2.fastq.gz

│ ├── barcodes

│ │ ├── barcode_whitelist.txt

│ │ └── generated_barcode_read_info_table.csv

│ ├── logs

│ │ ├── pipseeker_2023-05-25_16-53-40.log

│ │ └── progress.log

│ ├── metrics

│ │ └── barcode_stats.json

│ └── run_config.json

└── fastqs

├── RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz

├── RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R2_001.fastq.gz

├── RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L002_R1_001.fastq.gz

└── RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L002_R2_001.fastq.gz

The barcode/run_config.json told us that the example data was using the v3 chemistry. In the barcode/barcoded_fastqs/ directory, we can see that the original Read 1 reads were split into four different files. Let’s have a look:

$ zcat barcode/barcoded_fastqs/barcoded_1_R1.fastq.gz | head -20

@VH00284:1:AAANWCCHV:1:1101:63733:1057 1:N:0:GGCCTCCT+AGAGGATA

AGGCCAAAACCCCCAAGCGGACCTGAGT

+

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~CCCCCCCCCCCC

@VH00284:1:AAANWCCHV:1:1101:63960:1057 1:N:0:GGCCTCCT+AGAGGATA

ACCAAACCAGGACCATTTTGAACTCAGG

+

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~C--CCCCCCCCC

@VH00284:1:AAANWCCHV:1:1101:64415:1057 1:N:0:GGACTCCT+AGAGGATA

ACGGACTGACAGATCCATAGCCGGCCGG

+

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~CC;;CCCCCCCC

@VH00284:1:AAANWCCHV:1:1101:64869:1057 1:N:0:GGACTCCT+AGAGGATA

CATCACATAACCCCAGTAACGAAGTCAT

+

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~CCC;;-CC;CC-

@VH00284:1:AAANWCCHV:1:1101:57503:1076 1:N:0:GGCCTCCT+AGAGGATA

ACCCCCTAATCTAATCTGTGACGTTCCC

+

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~CCC!CCCCCCCC

Then how do those compare to the original reads? Let’s have a look at a few of them, starting with the first one: @VH00284:1:AAANWCCHV:1:1101:63733:1057:

$ zcat fastqs/RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz | grep -A 3 '@VH00284:1:AAANWCCHV:1:1101:63733:1057'

@VH00284:1:AAANWCCHV:1:1101:63733:1057 1:N:0:GGCCTCCT+AGAGGATA

TTGGGTCCATGCAACACGAGTTGGTATCGAGTGGGAAGTGCGGACCTGAGT

+

C;C!CCCCCCCCCCC-;CCCC;CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC!CCCCCCCCCCCCC

It seems the last 12-bp of the original reads together with the quality strings are preserved, and the beginning bases of the reads are “translated” into a 16-bp sequence and the quality strings are ignored. If we check a few more reads, we can confirm our observation. Therefore, we now can guess that the last 12-bp of the original reads are UMI, and the everything before the UMI should contain the cell barcode information.

Having messed around a bit, I failed to figure out how the “translation” works, so I decided to focus on the cell barcodes themselves. Checking the barcode/barcodes/barcode_whitelist.txt file:

$ wc -l barcode/barcodes/barcode_whitelist.txt

232682 barcode/barcodes/barcode_whitelist.txt

$ head barcode/barcodes/barcode_whitelist.txt

AAAAAAAAAACAATCC

AAAAAAAAAACCCCTC

AAAAAAAAAACGACAT

AAAAAAAAAATTAAAG

AAAAAAAAAATTAAGC

AAAAAAAAACACCATG

AAAAAAAAACAGACAT

AAAAAAAAACATATAC

AAAAAAAAACCGAGGC

AAAAAAAAACGACCAA

Here, we have a total of 232,682 whitelist barcodes, each with 16 bp in length. If we assume the cell barcodes consist of combinations of a fixed set of barcodes, we should be able to see the pattern by checking unique sequences. Since the whitelist barcodes are 16 bp, it is natural for us to think they are two 8-bp combinations. Are they?

$ cut -c 1-8 barcode/barcodes/barcode_whitelist.txt | sort -u | wc -l

9216

$ cut -c 9-16 barcode/barcodes/barcode_whitelist.txt | sort -u | wc -l

9216

This means there are 9,216 unique sequences in the first 8 bp and 9,216 unique sequences in the last 8 bp, which seems to be too high as a per round barcode number. However, we notice that $9,216 = 96 \times 96$. Therefore, it is more likely that the 16-bp barcode consists of four parts, each with 96 unique 4-bp barcodes:

$ cut -c 1-4 barcode/barcodes/barcode_whitelist.txt | sort -u | wc -l

96

$ cut -c 5-8 barcode/barcodes/barcode_whitelist.txt | sort -u | wc -l

96

$ cut -c 9-12 barcode/barcodes/barcode_whitelist.txt | sort -u | wc -l

96

$ cut -c 13-16 barcode/barcodes/barcode_whitelist.txt | sort -u | wc -l

96

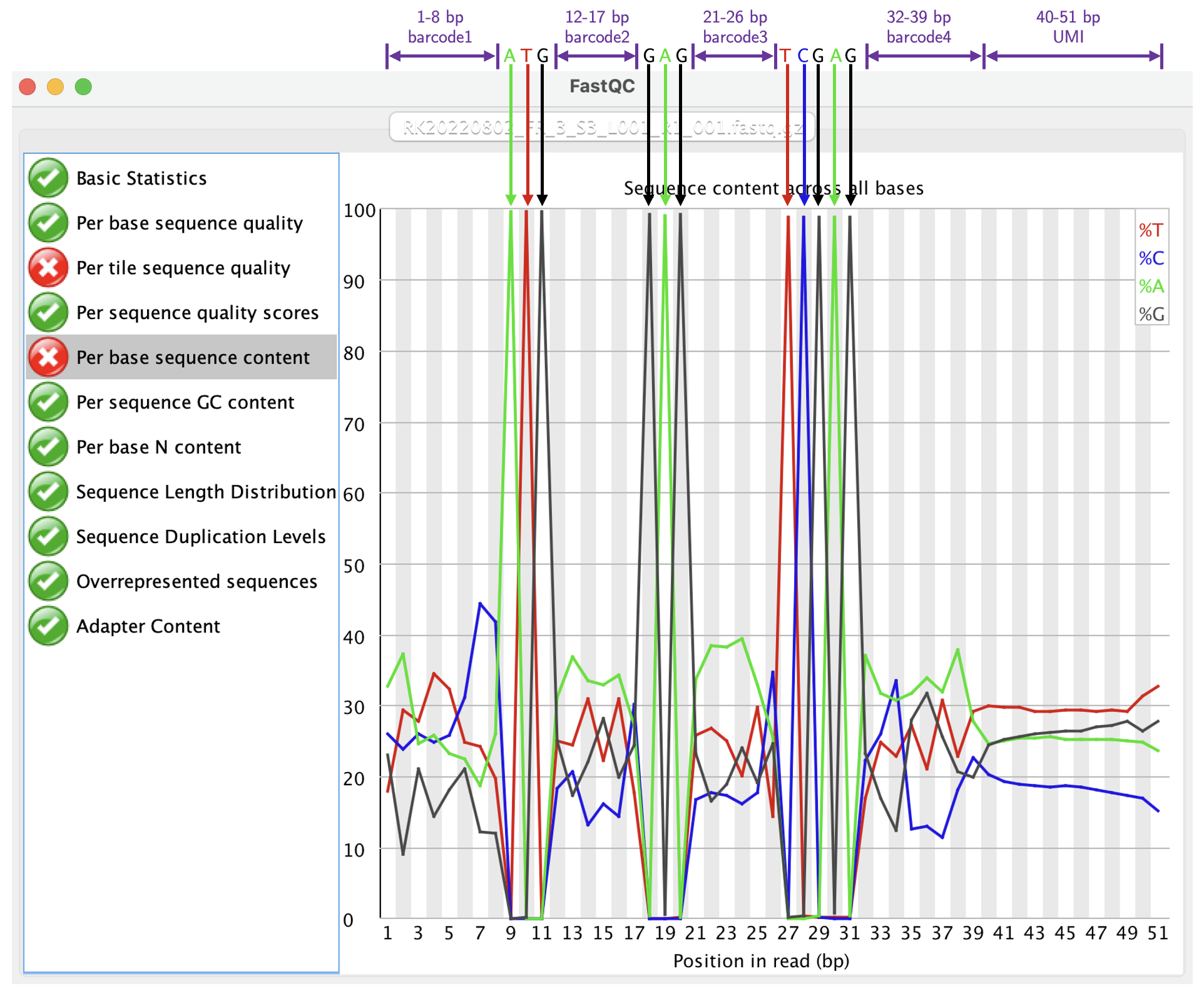

That is indeed the case, and it was consistent with the method section of the Clark2023 paper. Now we are confident that the whitelist cell barcodes are the combinations of four sets of 4-bp “translated” barcodes, with 96 unique barcodes in each set. In order to achieve this experimentally, there must be some common sequences, a.k.a linkers or splints or whatever you call them, in between each set of the barcodes. If this is the case, FastQC would tell us. Checking one of the R1 file, we have:

Now it is clear to us that the identify of each base in Read 1:

| Base positions | Identity |

|---|---|

| 1 - 8 | barcode1 (8 bp) |

| 9 - 11 | ATG |

| 12 - 17 | barcode2 (6 bp) |

| 18 - 20 | GAG |

| 21 - 26 | barcode3 (6 bp) |

| 27 - 31 | TCGAG |

| 32 - 39 | barcode4 (8 bp) |

| 40 - 51 | UMI (12 bp) |

Based on our previous results, in the original reads before “translation”, there should be 96 unique 8-bp barcode1, 96 unique 6-bp barcode2, 96 unique 6-bp barcode3 and 96 unique 8-bp barcode4. The combination of them forms a cell barcode. Now let’s find out the unique sequences in each set:

zcat fastqs/RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz | \

sed -n '2~4 p' | \

cut -c 1-8 | \

sort | uniq -c | \

sort -b -k1,1nr | \

less -N

We see all unique 8-mers in the first 8 bp of Read 1, sorted by occurrences in descending order. You see, the occurrences of the top 96 8-mers are comparable, but there is a sudden drop (two orders of magnitude) from 96th to 97th 8-mers. It indicates that the top 96 8-mers are our whitelist, and the rest are probably mismatches due to sequencing and PCR errors etc. Here are the lines 94 - 98 of the output:

| |

In the same way, we can use the above commands and change cut -c 1-8 to 12-17, 21-26 and 31-39 to check the other three barcodes, which yields similar results. Therefore, we can obtain the four sets of barcodes like this:

# get barcode1 (8 bp)

zcat fastqs/RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz | \

sed -n '2~4 p' | \

cut -c 1-8 | \

sort | uniq -c | \

sort -b -k1,1nr | \

head -96 | \

awk '{print $2}' > fb_v3_bc1.tsv

# get barcode2 (6 bp)

zcat fastqs/RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz | \

sed -n '2~4 p' | \

cut -c 12-17 | \

sort | uniq -c | \

sort -b -k1,1nr | \

head -96 | \

awk '{print $2}' > fb_v3_bc2.tsv

# get barcode3 (6 bp)

zcat fastqs/RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz | \

sed -n '2~4 p' | \

cut -c 21-26 | \

sort | uniq -c | \

sort -b -k1,1nr | \

head -96 | \

awk '{print $2}' > fb_v3_bc3.tsv

# get barcode4 (8 bp)

zcat fastqs/RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz | \

sed -n '2~4 p' | \

cut -c 32-39 | \

sort | uniq -c | \

sort -b -k1,1nr | \

head -96 | \

awk '{print $2}' > fb_v3_bc4.tsv

On top of that, by checking the manual of the FluentBio kits, we finally figure out the library structure of PIPseq$^{\textmd{TM}}$ V3. The HTML representation is here, and the seqspec specification is here.

Validation

Now we need to do some sanity check and validation. First, according to their manual, the Read 2 adapters are added via A-tailing and ligation. In this case, all Read 2 should start with T. Let’s check:

zcat RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R2_001.fastq.gz | \

sed -n '2~4 p' | \

cut -c 1 | \

sort | uniq -c

#### The output is

182181 A

27462 C

97214 G

62401662 T

The result seems to be consistent with our expectation. In addition, A appears many more times than C and G. There might be a reason for that, but I will leave it for now.

Next, we should do some more appropriate validation. We use STARsolo to analyse the data. Since we know the library structure and whitelist, we can do this relatively easily:

STAR --runThreadN 8 \

--genomeDir /data/bio-chenx/reference/others/hs_mm_mix/refdata-gex-GRCh38-and-mm10-2020-A/star_2.7.9a \

--readFilesCommand zcat \

--outFileNamePrefix ./star_outs/RK20220802/ \

--readFilesIn fastqs/RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R2_001.fastq.gz fastqs/RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz \

--soloType CB_UMI_Complex \

--soloCBposition 0_0_0_7 0_11_0_16 0_20_0_25 0_31_0_38 \

--soloUMIposition 0_39_0_50 \

--soloCBwhitelist fb_v3_bc1.tsv fb_v3_bc2.tsv fb_v3_bc3.tsv fb_v3_bc4.tsv \

--soloCBmatchWLtype 1MM \

--soloCellFilter EmptyDrops_CR \

--outSAMattributes CB UB \

--outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate

Once it is finished, you can check the summary:

$ star_outs/RK20220802/Solo.out/Gene/Summary.csv

Number of Reads,62708519

Reads With Valid Barcodes,0.973692

Sequencing Saturation,0.324326

Q30 Bases in CB+UMI,0.940079

Q30 Bases in RNA read,0.906632

Reads Mapped to Genome: Unique+Multiple,0.892956

Reads Mapped to Genome: Unique,0.640405

Reads Mapped to Gene: Unique+Multipe Gene,0.790096

Reads Mapped to Gene: Unique Gene,0.753377

Estimated Number of Cells,3736

Unique Reads in Cells Mapped to Gene,41294018

Fraction of Unique Reads in Cells,0.874074

Mean Reads per Cell,11053

Median Reads per Cell,10017

UMIs in Cells,27820058

Mean UMI per Cell,7446

Median UMI per Cell,6810

Mean Gene per Cell,1678

Median Gene per Cell,1667

Total Gene Detected,31436We see that more than 97% of the barcodes are valid (in the whitelist), which is good. Since the whitelist is generated using the species mixing data, it is not surprising that they match. Now let’s check the PBMC data from a healthy individual using the T20 kit as an independent validation. Download the FASTQ files into the fastqs directory. Then:

STAR --runThreadN 8 \

--genomeDir /data/bio-chenx/reference/homo_sapiens/refdata-gex-GRCh38-2020-A/star_2.7.9a \

--readFilesCommand zcat \

--outFileNamePrefix ./star_outs/PH20220718/ \

--readFilesIn fastqs/RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R2_001.fastq.gz fastqs/RK20220802_FR_3_S3_L001_R1_001.fastq.gz \

--soloType CB_UMI_Complex \

--soloCBposition 0_0_0_7 0_11_0_16 0_20_0_25 0_31_0_38 \

--soloUMIposition 0_39_0_50 \

--soloCBwhitelist fb_v3_bc1.tsv fb_v3_bc2.tsv fb_v3_bc3.tsv fb_v3_bc4.tsv \

--soloCBmatchWLtype 1MM \

--soloCellFilter EmptyDrops_CR \

--outSAMattributes CB UB \

--outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate

Again, check the result summary of the PBMC sample:

$ cat star_outs/PH20220718/Solo.out/Gene/Summary.csv

Number of Reads,62708519

Reads With Valid Barcodes,0.973816

Sequencing Saturation,0.316913

Q30 Bases in CB+UMI,0.940079

Q30 Bases in RNA read,0.906632

Reads Mapped to Genome: Unique+Multiple,0.588755

Reads Mapped to Genome: Unique,0.457185

Reads Mapped to Gene: Unique+Multipe Gene,0.464126

Reads Mapped to Gene: Unique Gene,0.457105

Estimated Number of Cells,2861

Unique Reads in Cells Mapped to Gene,23771638

Fraction of Unique Reads in Cells,0.829309

Mean Reads per Cell,8308

Median Reads per Cell,6598

UMIs in Cells,16151901

Mean UMI per Cell,5645

Median UMI per Cell,4564

Mean Gene per Cell,1191

Median Gene per Cell,1145

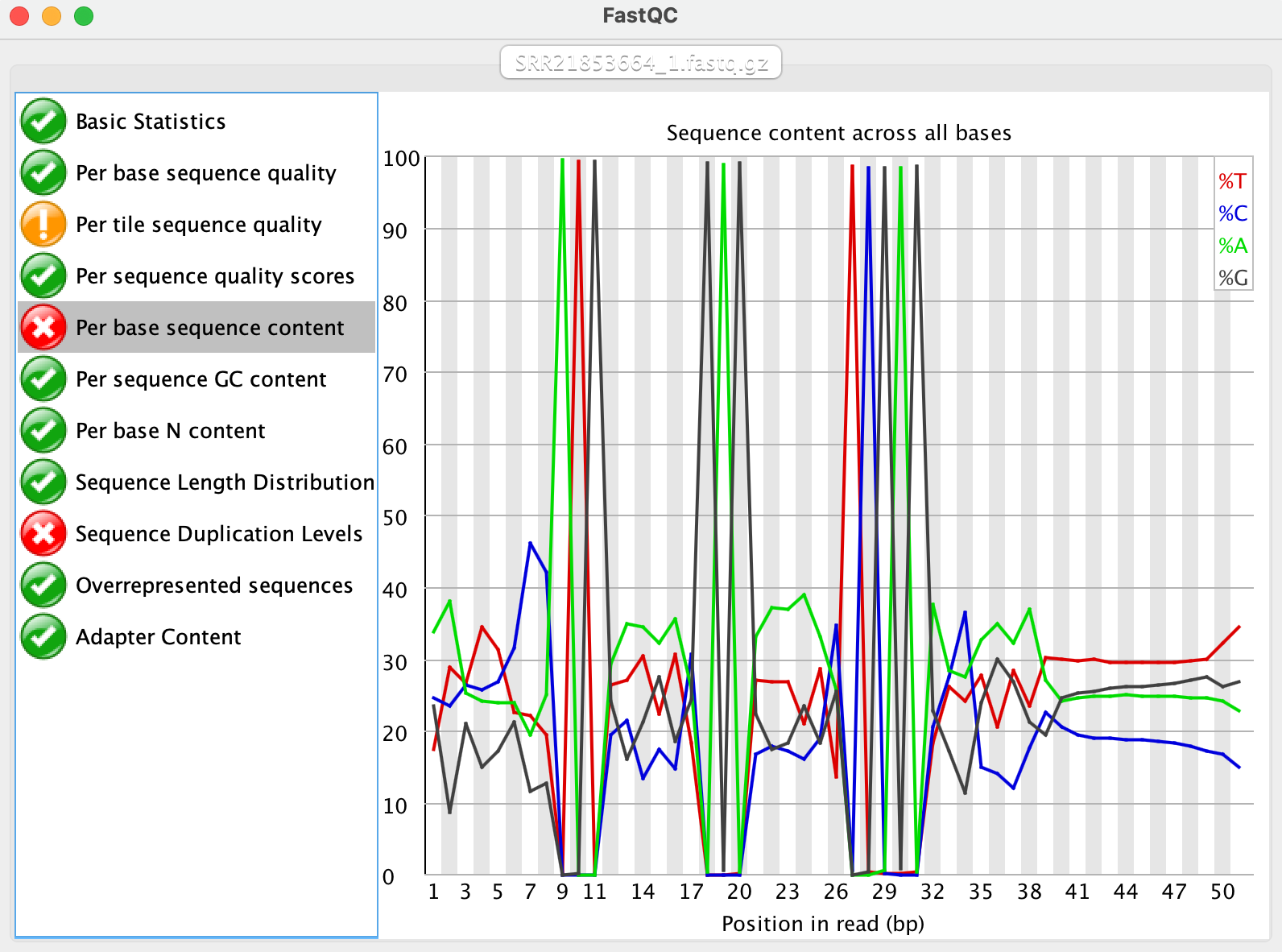

Total Gene Detected,17472We still see more than 97% of the barcodes are valid. Then we realised that many samples from the Clark2023 paper were actually using the FluentBio kit, not the first few samples I mentioned earlier in this post. Take SRR21853664 as an example, the FastQC results seems extremely similar:

We should be able to use the same STAR command and the same whitelist files to process the data:

STAR --runThreadN 8 \

--genomeDir /data/bio-chenx/reference/homo_sapiens/refdata-gex-GRCh38-2020-A/star_2.7.9a \

--readFilesCommand zcat \

--outFileNamePrefix ./star_outs/SRR21853664/ \

--readFilesIn fastqs/SRR21853664_2.fastq.gz fastqs/SRR21853664_1.fastq.gz \

--soloType CB_UMI_Complex \

--soloCBposition 0_0_0_7 0_11_0_16 0_20_0_25 0_31_0_38 \

--soloUMIposition 0_39_0_50 \

--soloBarcodeReadLength 0 \

--soloCBwhitelist fb_v3_bc1.tsv fb_v3_bc2.tsv fb_v3_bc3.tsv fb_v3_bc4.tsv \

--soloCBmatchWLtype 1MM \

--soloCellFilter EmptyDrops_CR \

--outSAMattributes CB UB \

--outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate

Check the result summary of SRR21853664:

$ cat star_outs/SRR21853664/Solo.out/Gene/Summary.csv

Number of Reads,24696002

Reads With Valid Barcodes,0.973371

Sequencing Saturation,0.78488

Q30 Bases in CB+UMI,0.955722

Q30 Bases in RNA read,0.942888

Reads Mapped to Genome: Unique+Multiple,0.703656

Reads Mapped to Genome: Unique,0.57576

Reads Mapped to Gene: Unique+Multipe Gene,0.6014

Reads Mapped to Gene: Unique Gene,0.59319

Estimated Number of Cells,2472

Unique Reads in Cells Mapped to Gene,8871000

Fraction of Unique Reads in Cells,0.605553

Mean Reads per Cell,3588

Median Reads per Cell,2702

UMIs in Cells,1754338

Mean UMI per Cell,709

Median UMI per Cell,560

Mean Gene per Cell,287

Median Gene per Cell,260

Total Gene Detected,13157Things also checkout. We also tested SRR19184609 and SRR19184609. We are sure there are other samples using the same version. We can also figure out how PIPseeker$^{\textmd{TM}}$ “translates” the original cell barcodes (8 + 6 + 6 + 8 bp) into their own format (4 + 4 + 4 + 4 bp) by comparing the fb_v3_bc{1..4}.tsv files with their output, but I will leave it for now.

For other mysterious samples, we will continue in the next post.