I first came across with the normal distribution when I was 17 years old in high school. The probability density function (PDF) is

$$f_{\boldsymbol{X}}(x) = \cfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}\,e^{-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}}$$

where $\mu$ and $\sigma$ are the population mean and standard deviation, respectively.

Like most people when they first came across this function, the derivation of the function was not really introduced. Soon after that, we started to use it to calculate probabilities and other things. However, where does it come from? What’s the intuition of the function? Why are two of the most important constants $\pi$ and $e$ there? Those questions lingered in my brain ever since.

Now, 20 years later, it is easy to use internet to do some research. You can find a lot of material about the derivation, such as those YouTube videos and the StackExchange post listed in the References section. However, the problem is that they all use this “dart throwing” example to begin with the derivation, without explaining why the example is chosen in the first place and why it eventually leads to the normal distribution.

Then I realise that perhaps the most intuitive way of seeing where the normal distribution comes from is actually follow the history to see how the normal distribution is derived naturally.

Having done some reading, it seems there are two independent thoughts of getting the normal PDF:

- People wanted to find an approximation to the binomial distribution, because it was difficult to compute the factorials.

- There seemed to be a pattern on measurement errors in astronomy, and people wanted to find a function, so called the error curve, to describe the errors.

I’m writing this post to help myself understand the procedures, which might be useful to those who are interested as well.

As An Approximation To The Binomial

The story goes like many mathematicians were working on gambling-related problems. They used binomial distributions a lot. Calculating the binomial coefficients was difficult, apparently, due to the complexity of factorials. They noticed that when $n$ in the binomial distribution became large, the shape of the binomial distribution became a bell-shaped curve. They wanted to find the equation of the curve to avoid the calculation of factorials. The French mathematician Abraham de Moivre started working on that in 1721. In 1733, using an factorial approximation (today known as the Stirling’s Formula), he found out that in the symmetrical case ($p=\frac{1}{2}$) of a binomial distribution, the probabilities around the central terms can be approximated by:

$$\binom{n}{\frac{n}{2}+d}\left(\cfrac{1}{2}\right)^n \approx \cfrac{2}{\sqrt{2\pi n}}\,e^{-\frac{2d^2}{n}}$$

where $d$ is some integer. Later on, the French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace took a step further and extended the approximation to asymmetrical binomials by introducing a correction term. Eventually, it gives what we known today as the De Moivre–Laplace Theorem:

$$\binom{n}{k}p^k q^{n-k} \approx \cfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi npq}}\,e^{-\frac{(k-np)^2}{2npq}} \textmd{ , where } p+q=1,p,q > 0$$

which is very similar to the normal PDF. The proof of the above theorem can be found in this Wikipedia page. In order to understand the proof, you need to know Stirling’s formula:

$$n! \approx \sqrt{2\pi n} \left( \cfrac{n}{e} \right)^n $$

In addition, you also need to be familiar with the following Taylor expansion:

$$\ln(1+x) = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n+1}\cfrac{x^n}{n} = x - \cfrac{x^2}{2} + \cfrac{x^3}{3} - \cfrac{x^4}{4} + \cdots $$

That’s all you need to know. The rest are basically algebraic manipulation, and you just have to be patient.

Though intuitive and a great discovery, I still feel something is missing after seeing the proof. First, it is not in the form of the normal PDF that we are using today. In addition, if it is merely an approximation to the binomial, we would just use it as a tool to assist calculation, which renders it useless in the age of computers.

Therefore, I’m not quite satisfied by this derivation.

The Error Curve

I only realised recently that the most intuitive way of deriving the normal PDF is right there in the book Theoria motus corporum coelestium in sectionibus conicis solem ambientium (Theory of the Motion of the Heavenly Bodies Moving about the Sun in Conic Sections) by the legendary Carl Friedrich Gauss. In the section Determination of an Orbit satisfying as nearly as possible any number of Observations whatever, Gauss detailed the procedures how he found the function that described the behaviour of random errors, that is, the error curve which is essentially the normal distribution we know.

The symbols, notations and some words are a bit different from what we are using today. At least I’m not familiar with them. Therefore, I do not fully understand it. I have only got some vague ideas, but I can already tell it is much more intuitive and natural to follow. After reading The Evolution of the Normal Distribution by Prof. Saul Stahl and other useful articles in the References section at the end of this post, I am convinced that the most intuitive and natural way of deriving the normal PDF is probably the Gaussian way.

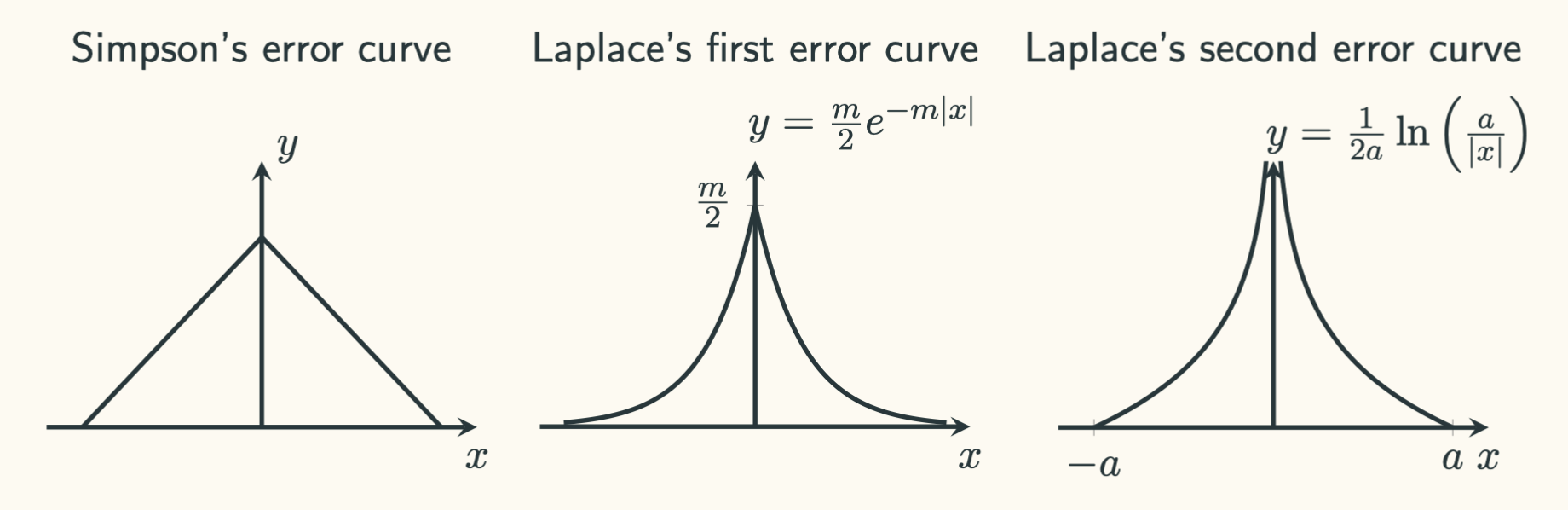

In his book, Gauss derived the normal PDF as the error curve. “Inventing” or finding the error curve is difficult. Many tried and got it wrong. Here are a few examples from Thomas Simpson and Pierre Simon Laplace:

However, following Gauss’ thoughts to derive the normal PDF is not that difficult. We just need to get familiar about the historical context and be very clear about the assumptions people had back then about errors.

Assumptions About Errors Around & Before Gauss’ Time

Back in the days, many astronomers were trying to measure and predict the trajectories and positions of different planets and stars. They were well aware that their measurements had errors due to the observers, the instruments and many other factors. Even for the same object, they had distinct observations. In this context, an error refers to the difference between the measurement and the real location. Around the end of the 16th century, Tycho Brahe, the astronomer known for his accurate astronomical observations, incorporated repeated measurements into his methodology, a practice adopted by many astronomers. Surprisingly, he did not really specify how he converted those different measurements into a single representative value to represent the true location of an object. Did he use the mean? Did he use the median? Or did he just choose one that he saw fit? We do not know.

Galileo Galilei is thought to be the first person who proposed a systematic analysis of errors in writing. In his work Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, Ptolemaic and Copernican in 1632, Galileo informally discussed what he called “observational errors”, which is basically what is called “distribution of random errors” today. He provided a few statements or assumptions based on accumulated astronomical data. The relevant ones to this post which I took from Hald 1986 are:

- The observations are distributed symmetrically about the true value; that is, the errors are distributed symmetrically about zero.

- Small errors occur more frequently than large errors

Note that there were no formal and solid proofs for those assumptions. They had been thought to be true based on the data accumulated in the past. The data seemed to support those two assumptions. In addition, they had been intuitive as well. For example, if an instrument is designed meticulously to measure the location of a planet or star, it is more likely for us to obtain a measurement around the true location. Just like when we draw a good random sample from a population, the sample is a micro-version of the population and we should not expect the sample to deviate too much from the population. If errors are random, they should be equally likely to be positively and negatively deviating from the true value.

There seemed to be some patterns of errors. In order to systematically analyse errors, people wanted to find the error curve to describe the errors. Using the terms in a modern probability course, they wanted to find the PDF of the error, since the error is apparently continuous.

How Did Gauss Do It?

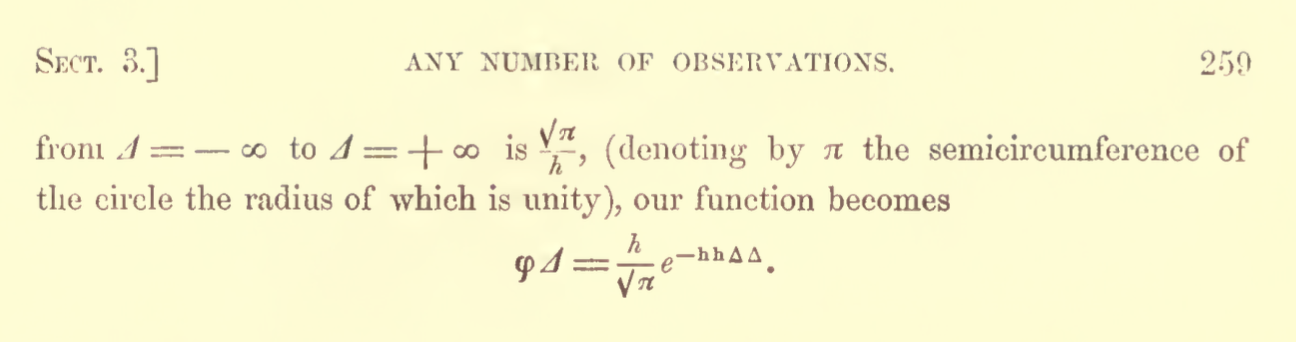

Gauss was among one of those people trying to find the error curve. In his seminal work Theoria motus corporum coelestium in sectionibus conicis solem ambientium (Theory of the Motion of the Heavenly Bodies Moving about the Sun in Conic Sections), Gauss used the idea of maximum likelihood estimation (well … not exactly1) and his educational guess to derive the following prototype:

where $\Delta$ is the error, which is basically $x-\mu$ in modern terms, and $h$ is a constant that “can be considered as the measure of precision of the observations”2.

Now let’s briefly and partially3 reproduce Gauss’ derivation. In terms of notations and symbols, we will stick to the conventions of modern probability textbooks where we use capital letters ($W,X,Y,Z$ etc.) to represent random variables themselves and use small letters ($w,x,y,z$ etc.) to represent the values of the random variables.

First, we let the true location of an object of interest be $m$. Then we have some repeated measurements $X_1,X_2,\cdots,X_{n-1},X_n$, and we know they all have some errors. Let’s denote the error using the capital Greek letter $\Epsilon$ (Epsilon). We have $\Epsilon_i = X_i - m$. We think the errors have some pattern that can be described by an unknown PDF: $f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon)$.

Based on the two assumptions mentioned above, we have already known some properties of the PDF. Assumption 1 tells us that:

$$f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon) = f_{\Epsilon}(-\varepsilon)$$

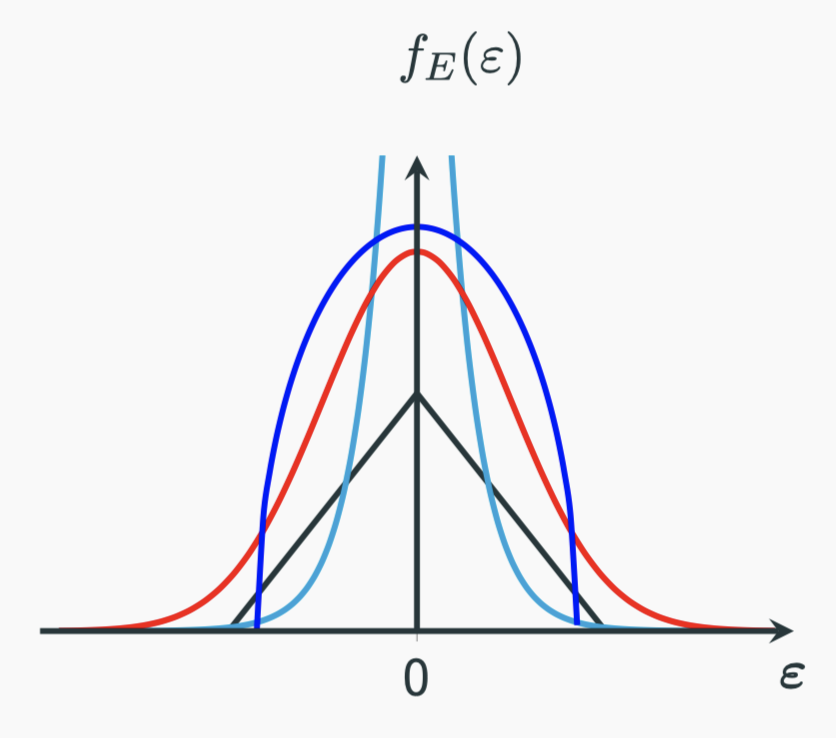

which means $f_{\Epsilon}$ is an even function. Assumptions 2 tells us that the closer $\varepsilon$ to zero, the more likely it will occur. We can roughly see the shape of the function as something like these curves:

Now that we have a set of repeated measures $x_1,x_2,\cdots,x_{n-1},x_n$ that yield a set of errors $\varepsilon_i = x_i - m$. We can construct the likelihood function on this set of data like this:

$$\mathcal{L} = \prod_{i=1}^n f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon_i)$$

The log likelihood function is:

$$\ell = \sum_{i=1}^{n}\ln f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon_i)$$

Basically, we want to maximise the log likelihood function $\ell$. Therefore, we should let $\ell^{\prime} = \cfrac{\mathrm{d}\ell}{\mathrm{d}\varepsilon}=0$. Recall that $\left(\ln x\right)^{\prime} = \cfrac{1}{x}$. Using the chain rule, we have $\left[\ln f(x)\right]^{\prime} = \cfrac{f^{\prime}(x)}{f(x)}$. Then the derivative of our log likelihood function becomes:

$$\ell^{\prime} = \left[ \sum_{i=1}^n \ln f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon_i) \right]^{\prime} = \sum_{i=1}^{n}\cfrac{f_{\Epsilon}^{\prime}(\varepsilon_i)}{f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon_i)} $$

For simplicity, we let $g_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon) = \cfrac{f_{\Epsilon}^{\prime}(\varepsilon)}{f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon)}$. Then $\ell^{\prime}$ becomes:

$$ \begin{aligned} \begin{align*} \ell^\prime &= \sum_{i=1}^{n}g_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon_i) \\ &= g_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon_1) + g_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon_2) + \cdots + g_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon_{n-1}) + g_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon_n) \\ &= g_{\Epsilon}(x_1 - m) + g_{\Epsilon}(x_2 - m) + \cdots + g_{\Epsilon}(x_{n-1} - m) + g_{\Epsilon}(x_n - m) \tag{1} \end{align*} \end{aligned} $$

In a typical case of maximum likelihood estimation, we know the PDF, we just need to figure out $m$ such that $\ell^\prime = 0$. In this case, we also want to let $\ell^\prime = 0$, but we know neither the PDF ($\boldsymbol{g}$ or $\boldsymbol{f}$) nor $m$. What should we do here?

Well, Gauss thinks that in order for $\ell^\prime = 0$, $m$ must take the value of the arithmetic mean of those measurements we have. Using the terms we normally use when dealing with estimators or estimates, it means:

$$\hat{m} = \cfrac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i$$

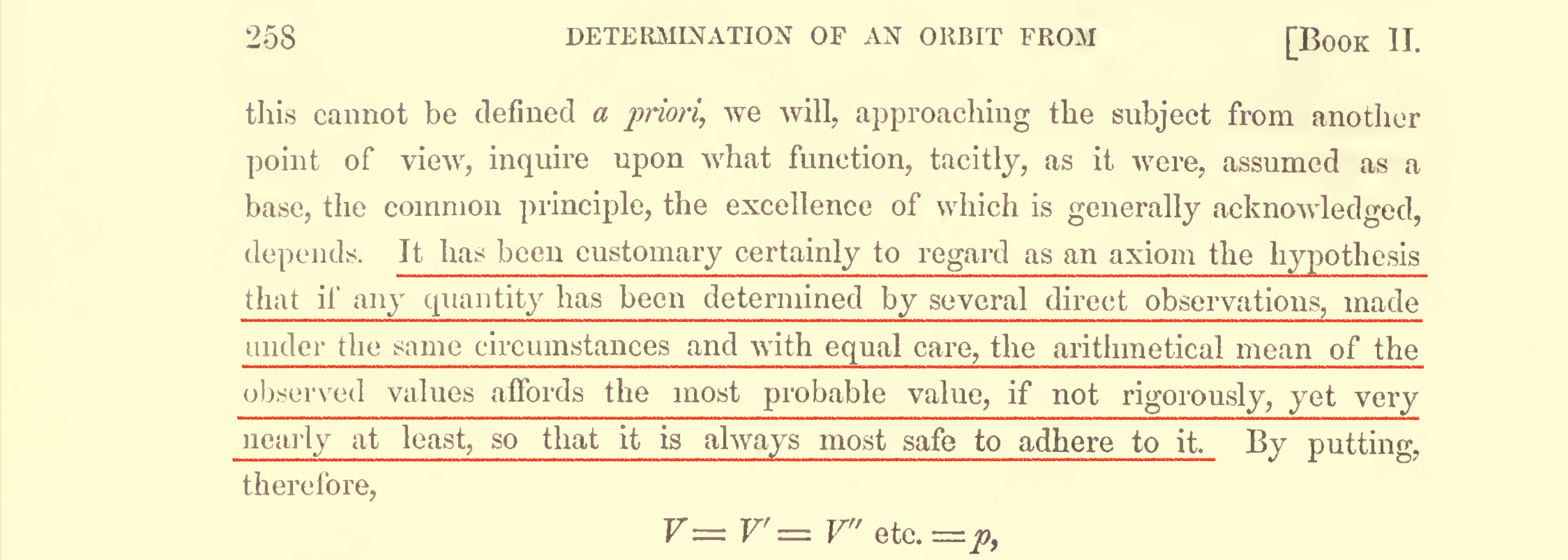

There was no formal proof that the above statement was true. It is just Gauss’ educational guess. Here I quote from Gauss’ original words (well … not really “original” but the translated version from page 258):

… It has been customary certainly to regard as an axiom the hypothesis that if any quantity has been determined by several direct observations, made under the same circumstances and with equal care, the arithmetical mean of the observed values affords the most probable value, if not rigorously, yet very nearly at least, so that it is always most safe to adhere to it …

The more I read, the more I realise that mathematics is not always about calculations, symbols, formulae and proofs etc. Sometimes, you need some good intuition and guesses, and it is those intuition that helps us understand a problem deeper.

You may not think it was a big deal for Gauss to make that guess, because it is … intuitive …, right? Actually, it was not so obvious or intuitive that the mean should be used back then. The history of people getting used to the mean is long and complicated. You can check this interesting article.

Now back to our work. We need to let $\ell^\prime = 0$. Using Gauss’ guess to replace $m$ with $\bar{x}$ in equation $(1)$, we have:

$$ g_{\Epsilon}(x_1 - \bar{x}) + g_{\Epsilon}(x_2 - \bar{x}) + \cdots + g_{\Epsilon}(x_{n-1} - \bar{x}) + g_{\Epsilon}(x_n - \bar{x}) = 0 \tag{2}$$

where $\bar{x}$ is the arithmetic mean of our measurements.

Equation $(2)$ must be true for any $n$ measurements. Therefore, if we let:

$$ x_1 = m \textmd{, \ \ and \ \ } x_2 = x_3 = x_4 = \cdots = x_{n-1} = x_n = m - nN$$

where $N$ is just some constant number. Then we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} \bar{x} &= \cfrac{x_1 + x_2 + \cdots + x_{n-1} + x_n}{n}\\[10pt] &= \cfrac{m + (m - nN) + (m - nN) + \cdots + (m - nN)}{n}\\[10pt] &= \cfrac{m + (n-1) \cdot (m-nN) }{n}\\[10pt] &= m-(n-1)N \end{aligned} $$

Putting those values back into equation $(2)$, we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} & g_{\Epsilon}(x_1 - \bar{x}) + g_{\Epsilon}(x_2 - \bar{x}) + \cdots + g_{\Epsilon}(x_{n-1} - \bar{x}) + g_{\Epsilon}(x_n - \bar{x}) = 0 \\[12.5pt] \Rightarrow & g_{\Epsilon}[m - (m-(n-1)N)] + g_{\Epsilon}[(m - nN) - (m-(n-1)N)] + \cdots + & \\ & g_{\Epsilon}[(m - nN) - (m-(n-1)N)] + g_{\Epsilon}[(m - nN) - (m-(n-1)N)] = 0 \\[12.5pt] \Rightarrow & g_{\Epsilon}[(n-1)N] + g_{\Epsilon}(-N) + \cdots + g_{\Epsilon}(-N) + g_{\Epsilon}(-N) =0 \\[12.5pt] \end{aligned} $$

Note that $g_{\Epsilon}(x_2-\bar{x}) = g_{\Epsilon}(x_3-\bar{x}) = \cdots = g_{\Epsilon}(x_n-\bar{x}) = g_{\Epsilon}(-N)$. There are $n-1$ of them, so we have:

$$g_{\Epsilon}[(n-1)N] + (n-1)g_{\Epsilon}(-N) = 0 \tag{3}$$

Now recall that Assumption 1 tells us that $f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon) = f_{\Epsilon}(-\varepsilon)$, meaning that it is an even function, so we have4:

$$f_{\Epsilon}^{\prime}(\varepsilon) = -f_{\Epsilon}^{\prime}(-\varepsilon)$$

Dividing $f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon)$ at the left-hand side and dividing $f_{\Epsilon}(-\varepsilon)$ at the right-hand side, we have:

$$\cfrac{f_{\Epsilon}^{\prime}(\varepsilon)}{f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon)} = - \cfrac{f_{\Epsilon}^{\prime}(-\varepsilon)}{f_{\Epsilon}(-\varepsilon)}$$

That means $g_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon) = -g_{\Epsilon}(-\varepsilon)$, and hence $g_{\Epsilon}(-N) = -g_{\Epsilon}(N)$. Putting this back to equation $(3)$:

$$g_{\Epsilon}[(n-1)N] - (n-1)g_{\Epsilon}(N) = 0$$

Move the second term to the other side of the equation:

$$g_{\Epsilon}[(n-1)N] = (n-1)g_{\Epsilon}(N)$$

Now we have a situation of $f(a\cdot x) = a\cdot f(x)$. In this case, $\cfrac{\Delta f(x)}{\Delta x}$ must be a constant. Therefore, $g_{\Epsilon}$ must be a linear function in the form:

$$g_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon) = k \cdot \varepsilon$$

where $k$ is some constant. Since $g_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon) = \cfrac{f_{\Epsilon}^{\prime}(\varepsilon)}{f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon)}$, we have:

$$ \cfrac{f_{\Epsilon}^{\prime}(\varepsilon)}{f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon)} = k \cdot \varepsilon \tag{4} $$

Again, recall that $ \left[ \ln f(x) \right] ^{\prime} = \cfrac{f^{\prime}(x)}{f(x)}$, so if we integrate both sides of equation $(4)$ with respect to $\varepsilon$, we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} & \int \cfrac{f_{\Epsilon}^{\prime}(\varepsilon)}{f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon)}\, \mathrm{d}\varepsilon = \int k \cdot \varepsilon \mathrm{d}\varepsilon\\[12.5pt] \Rightarrow & \ln f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon) = \cfrac{k}{2} \, \varepsilon^2 + c \end{aligned} $$

where $k,c$ are some constants. Therefore, we have:

$$ f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon) = e^{\frac{k}{2}\varepsilon^2 + c} = e^c \cdot e^{\frac{k}{2}\varepsilon^2} = Ae^{\frac{k}{2}\varepsilon^2} $$

where $A, k$ are some constants.

Finally, we are actually getting somewhere. Now we need to figure out the constants $A, k$.

Assumption 2 tells us that the smaller $\varepsilon$ is, the higher the chance it will occur. Therefore, the coefficient of $\varepsilon^2$ in the exponent of $e$ must be a negative number. Then we can let $\cfrac{k}{2} = -h^2$, where $h$ is some constant:

$$f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon) = Ae^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \tag{5}$$

Since equation $(5)$ is a PDF, when we integrate from $-\infty$ to $+\infty$, it must be equal to $1$. That is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f_{\Epsilon}(\varepsilon) \mathrm{d}\varepsilon &= 1 \\[10pt] \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} Ae^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \mathrm{d}\varepsilon &= 1 \\[10pt] A\int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \mathrm{d}\varepsilon &= 1 \end{aligned} $$

When Gauss was doing the derivation, Laplace had already worked out the following integral, which we called the Gausssian integrals today:

$$ \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} e^{-x^2} \mathrm{d}x = \sqrt{\pi} \textmd{ \ \ and \ \ } \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} e^{-a^2x^2} \mathrm{d}x = \cfrac{\sqrt{\pi}}{a} $$

There are many proofs out there. One of the most popular proof is by doing a double integral and converting to polar coordinates. It is highly likely that you have already come across it in the calculus class. If not, you can search it on the internet, which should be easy to find.

Anyway, Gauss used the results from Laplace, which he commented as “by the elegant theorem first discovered by LAPLACE”, and concluded $A = \cfrac{h}{\sqrt{\pi}}$. Therefore, the error curve that everybody had been looking for was:

$$\cfrac{h}{\sqrt{\pi}}\,e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2}$$

We can take a moment to ponder how beautiful the process and the final product is.

The Modern Form of The Normal PDF

The above PDF is still a bit different from what we are using today as a normal distribution. We still need a bit work to do to work out the value of $h$. That’s where the variance $\sigma^2$ comes in.

By definition, the expected value of the above PDF is:

$$\mathbb{E}[\Epsilon] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \varepsilon \cdot \cfrac{h}{\sqrt{\pi}}\,e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2}$$

It is easy to see that the above function is an odd function. If we integrate from $-\infty$ to $\infty$, eventually the area under the curve at the negative side and the positive side will cancel out5, so $\mathbb{E}[\Epsilon] = 0$.

Now we use $\sigma^2$ to denote the variance of the error: $\mathbb{V}\textmd{ar}(\Epsilon) = \sigma^2$. Again, by the common trick of calculating the variance, we have $\mathbb{V}\textmd{ar}(\Epsilon) = \mathbb{E}[\Epsilon^2] - (\mathbb{E}[\Epsilon])^2 = \mathbb{E}[\Epsilon^2] -0^2 = \mathbb{E}[\Epsilon^2]$. Basically, the variance is $\mathbb{E}[\Epsilon^2]$. Therefore, we have the following:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[\Epsilon^2] &= \sigma^2 \\ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \varepsilon^2 \cdot \cfrac{h}{\sqrt{\pi}}\,e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \mathrm{d}\varepsilon &= \sigma^2 \\[10pt] \cfrac{h}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \varepsilon^2 \cdot e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \mathrm{d}\varepsilon &= \sigma^2 \end{aligned} $$

Note that $\varepsilon^2 \cdot e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2}$ is an even function. Therefore, the above equation becomes6:

$$\cfrac{2h}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_{0}^{\infty} \varepsilon^2 \cdot e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \mathrm{d}\varepsilon = \sigma^2 \tag{6}$$

Recall the integration-by-parts technique tells us:

$$\int\boldsymbol{u}(x)\boldsymbol{v}^{\prime}(x) = \boldsymbol{u}(x)\boldsymbol{v}(x) - \int \boldsymbol{u}^{\prime}(x)\boldsymbol{v}(x)\mathrm{d}x$$

Also note that $\left( e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \right)^{\prime} = -2h^2 \varepsilon e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2}$. Now we could rewrite equation $(6)$ as follows:

$$ \cfrac{2h}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_{0}^{\infty} \left( -\cfrac{1}{2h^2}\, \varepsilon \right) \cdot \left( -2h^2 \varepsilon e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \right) \mathrm{d}\varepsilon = \sigma^2 \tag{7} $$

Now we can let $\boldsymbol{u}(\varepsilon) = -\cfrac{1}{2h^2}\, \varepsilon$ and $\boldsymbol{v}^{\prime}(\varepsilon) = -2h^2 \varepsilon e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2}$, and hence $\boldsymbol{v}(\varepsilon) = e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2}$. Using integration by parts, equation $(7)$ becomes:

$$ \begin{aligned} \cfrac{2h}{\sqrt{\pi}} \left( \left[ \left( -\cfrac{1}{2h^2}\, \varepsilon \right) \cdot \left( e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \right) \right]_{0}^{\infty} - \int_{0}^{\infty} -\cfrac{1}{2h^2} \cdot e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \right) &= \sigma^2 \\[10pt] \cfrac{2h}{\sqrt{\pi}} \left( \left[ -\cfrac{\varepsilon}{2h^2 e^{h^2\varepsilon^2}} \right]_{0}^{\infty} + \cfrac{1}{2h^2} \int_{0}^{\infty} e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \right)&= \sigma^2 \tag{8} \end{aligned} $$

Note there is a Gaussian integral in the second term in the parenthesis, so we can see that $\cfrac{1}{2h^2}\int_{0}^{\infty} e^{-h^2x^2} \mathrm{d}x = \cfrac{1}{2h^2} \cdot \cfrac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2h} = \cfrac{1}{4h^3} \sqrt{\pi}$. For the first term in the parenthesis, we can do:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left[ -\cfrac{\varepsilon}{2h^2 e^{h^2\varepsilon^2}} \right]_{0}^{\infty} &= \lim_{t \to \infty} \left[ -\cfrac{\varepsilon}{2h^2 e^{h^2\varepsilon^2}} \right]_{0}^{t} \\[12.5pt] &= \lim_{t \to \infty} \left( -\cfrac{t}{2h^2 e^{h^2t^2}} \right) - \left( -\cfrac{0}{2h^2 e^{h^2 \cdot 0^2}} \right) \\[12.5pt] &= - \lim_{t \to \infty} \left( \cfrac{t}{2h^2 e^{h^2t^2}} \right) - 0 \\[12.5pt] &= -\lim_{t \to \infty} \left( \cfrac{t}{2h^2 e^{h^2t^2}} \right) \end{aligned} $$

Here we have a situation of $\cfrac{\infty}{\infty}$. Using L’Hopital’s rule:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left[ -\cfrac{\varepsilon}{2h^2 e^{h^2\varepsilon^2}} \right]_{0}^{\infty} &= -\lim_{t \to \infty} \left( \cfrac{t}{2h^2 e^{h^2t^2}} \right) = -\lim_{t \to \infty} \left( \cfrac{t^\prime}{(2h^2 e^{h^2t^2})^\prime} \right) \\[12.5pt] &= -\lim_{t \to \infty} \left( \cfrac{1}{4h^4t e^{h^2t^2}} \right) = 0 \end{aligned} $$

Put those results back to equation $(8)$, we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} \cfrac{2h}{\sqrt{\pi}} \cdot \left( 0 + \cfrac{1}{4h^3} \sqrt{\pi} \right) &= \sigma^2 \\ \cfrac{1}{2h^2} &= \sigma^2\\ h &= \cfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}\sigma} \end{aligned} $$

Putting the value of $h$ back to Gauss error curve, we have:

$$\cfrac{h}{\sqrt{\pi}}\,e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} = \cfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}\,e^{-\frac{\varepsilon^2}{2\sigma^2}}$$

Note that the error is basically $x - m$, where $m$ is the true location. In our modern terms, it is basically the true mean $\mu$. Therefore, we have the general form of the normal PDF:

$$f_{X}(x) = \cfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}\,e^{-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}}$$

which is the PDF that we are using today!

Feedback

Do you find this is useful and intuitive? Do you spot any errors or ambiguities? Did I miss important references? I would like to hear your thoughts via email.

Thank you!

N.B.: in the original post, the Taylor expansion of $\ln(1+x)$ was written as $1 - \cfrac{x^2}{2} + \cfrac{x^3}{3} - \cdots$, which was a mistake. The first term should be $x$, NOT $1$. This has been corrected. Thank Mohsen Fayyaz for pointing this out for me.

References

- Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, Ptolemaic and Copernican

- Theory of the Motion of the Heavenly Bodies Moving about the Sun in Conic Sections

- Galileo’s Statistical Analysis of Astronomical Observations

- De Moivre’s Normal Approximation to the Binomial Distribution, 1733

- De Moivre-Laplace Theorem

- The Evolution of the Normal Distribution

- Gauss’s Derivation of the Normal Distribution and the Method of Least Squares, 1809

- Deriving The Normal Distribution Probability Density Function Formula

- Three Derivations of the Gaussian Distribution

- The shock of the mean: a missing element

- Maximum Likelihood Estimation

- YouTube videos on the derivation of the normal PDF: video 1 | video 2 | video 3

- StackExchange Post - How was the normal distribution derived?

There seems to be some confusion about whether Gauss used maximum likelihood estimation or least squares to derive the normal PDF. The two methods lead to the same estimate ($\bar{x}$), but they are based on different concepts. I’m not qualified to comment on this … yet … See Gauss’s Derivation of the Normal Distribution and the Method of Least Squares, 1809 in the References for more details. For now, let’s go with MLE to see how to derive the normal PDF. ↩︎

Those are Gauss’ original words translated. See the paper in the References section. ↩︎

The full and rigorous proof is actually more complicated than the content presented in this post. ↩︎

Think about the shape of an even function if you have trouble understanding this. ↩︎

Strictly speaking, what we should do here is $\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \varepsilon \cdot \cfrac{h}{\sqrt{\pi}}\,e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} = \int_{-\infty}^{0} \varepsilon \cdot \cfrac{h}{\sqrt{\pi}}\,e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} + \int_{0}^{\infty} \varepsilon \cdot \cfrac{h}{\sqrt{\pi}}\,e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2}$ and show they converge. ↩︎

Again, strictly speaking, we should do $\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \varepsilon^2 \cdot e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \mathrm{d}\varepsilon = \int_{-\infty}^{0} \varepsilon^2 \cdot e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \mathrm{d}\varepsilon + \int_{0}^{\infty} \varepsilon^2 \cdot e^{-h^2\varepsilon^2} \mathrm{d}\varepsilon$, and show they converge. ↩︎