Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is one of the gold standards to study protein-DNA interaction in vivo. In 1984, John Lis’ lab at Cornell invented the first ChIP method using UV to crosslink protein to DNA, and they used this approach to study the interaction of the RNA polymerase with specific genes (Gilmour and Lis, 1984). However, UV crosslinking causes DNA damage that makes cerntain downstream analysis, such as PCR, very difficult. Most people often choose to use another approach developed by Alexander Varshavsky’s lab later in 1988 at MIT, where they used formaldehyde for the crosslinking to study the histone-DNA interaction around the hsp70 gene (Solomon et al., 1988). Ever since then, the ChIP protocols have been optimised and developed extensively, with a lot of method variations invented along the way.

One major breakthrough came in 1999 and 2000, when two labs combined ChIP with microarray (ChIP-chip) to study protein-DNA interaction at the chromosome- and genome-wide scale. The first ChIP-chip was performed by Nancy Kleckner’ lab in 1999 to study cohesin binding along yeast chromosome III (Blat and Kleckner, 1999). One year later, Richard Young’s lab successfully investigated two transcription factors (Gal4p and Ste12p) across the entire yeast genome (Ren et al., 2000). With completion of the initial draft of the human genome and the development of microarray technologies, genome-wide tiling array in mouse and human became possible later on. Finally, people can profile in vivo protein-DNA interaction at the genome-wide scale in mouse and human using ChIP-chip. Then, next generation sequencing started. In 2007, Keji Zhao’s lab combined ChIP with Solexa (now Illumina) sequencing (ChIP-seq) to study the genome-wide distribution of 20 histone modifications, 1 histone variant (H2A.Z), Pol II and CTCF (Barski et al., 2007). Yes, that is the famous Barski et al. paper. It has 9 authors in total with 7 co-first authors listed alphabetically based on their surnames :-). ChIP-seq offers higher sensitivity and resolution over ChIP-chip, and it has now almost become a routine to study the function of DNA-binding proteins in vivo.

One key step in ChIP-seq is to fragment the genome to solubilise the chromatin and make the DNA fragments suitable for next generation sequencing. However, this turns out to be extremely difficult after formaldehyde crosslinking. Micrococcal nuclease (MNase) is a popular choice to fragment the genome. One problem with MNase is that it is only effective on native (non-crosslinked) chromatin, although people have successfully performed ChIP-seq using MNase on crosslinked cells (see e.g. Skene and Henikoff, 2015). The most popular approach to fragment chromatin is to use sonication to physically shear DNA into pieces. Several companies have even designed sonication machines specifically for the purpose of ChIP-seq. Those machines are quite popular in the ChIP-seq community based on my experience.

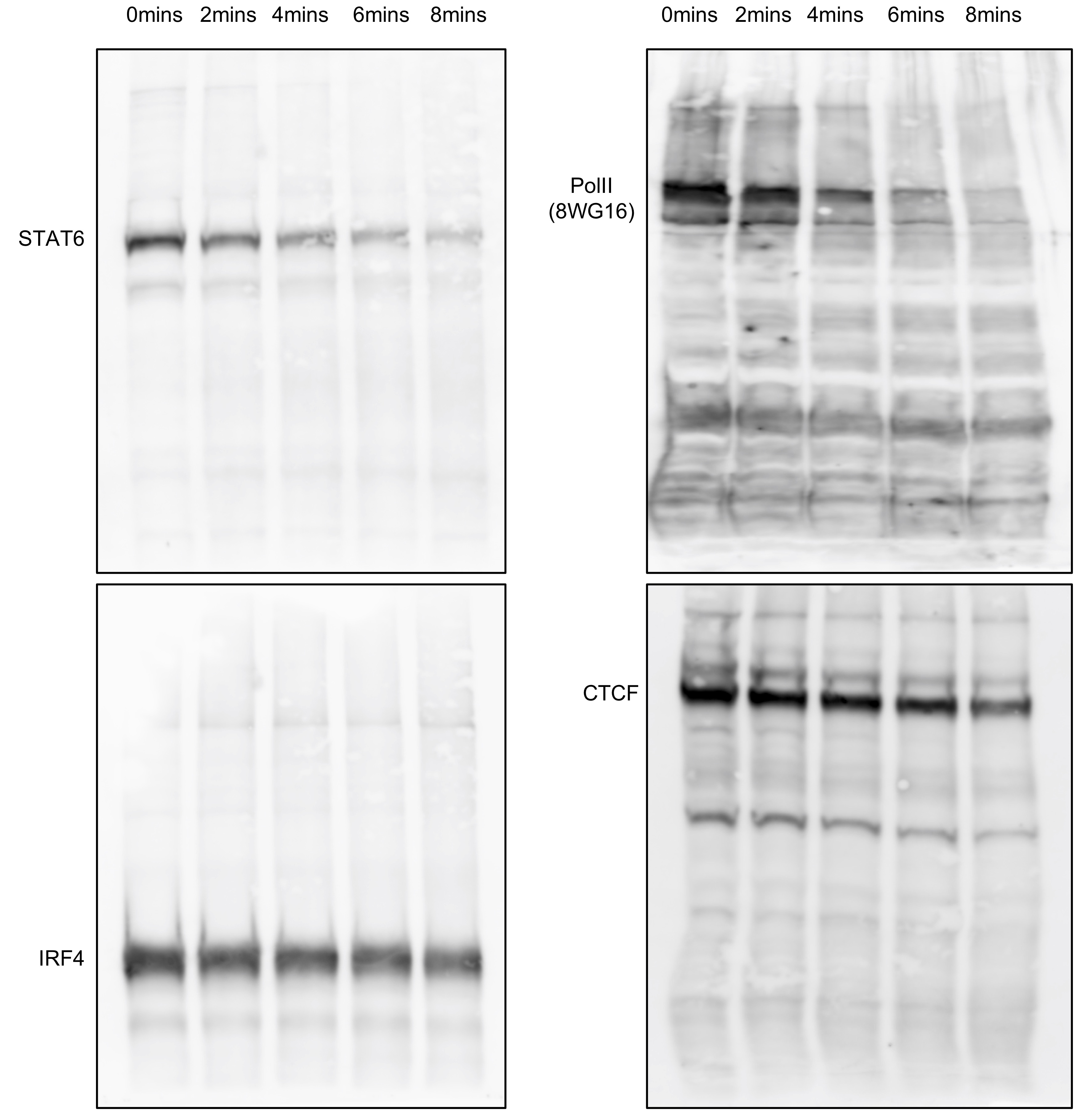

Sonication is really good at breaking down crosslinked chromatin, but it also has a really serious problem that many beginners do not know about: it occassionally also destroys the epitopes of your protein. We have a very efficient (in terms of shearing DNA into small pieces) sonication machine in the lab, and the results are kind of scary to me. I am not going to publish these results, so I might just as well to put them here. Below, you see a western blot with indicated antibodies on crosslinked chromatin. Equal amount of aliquots were taken out after indicated sonication intervals to run on a 8% polyacrylamide gel.

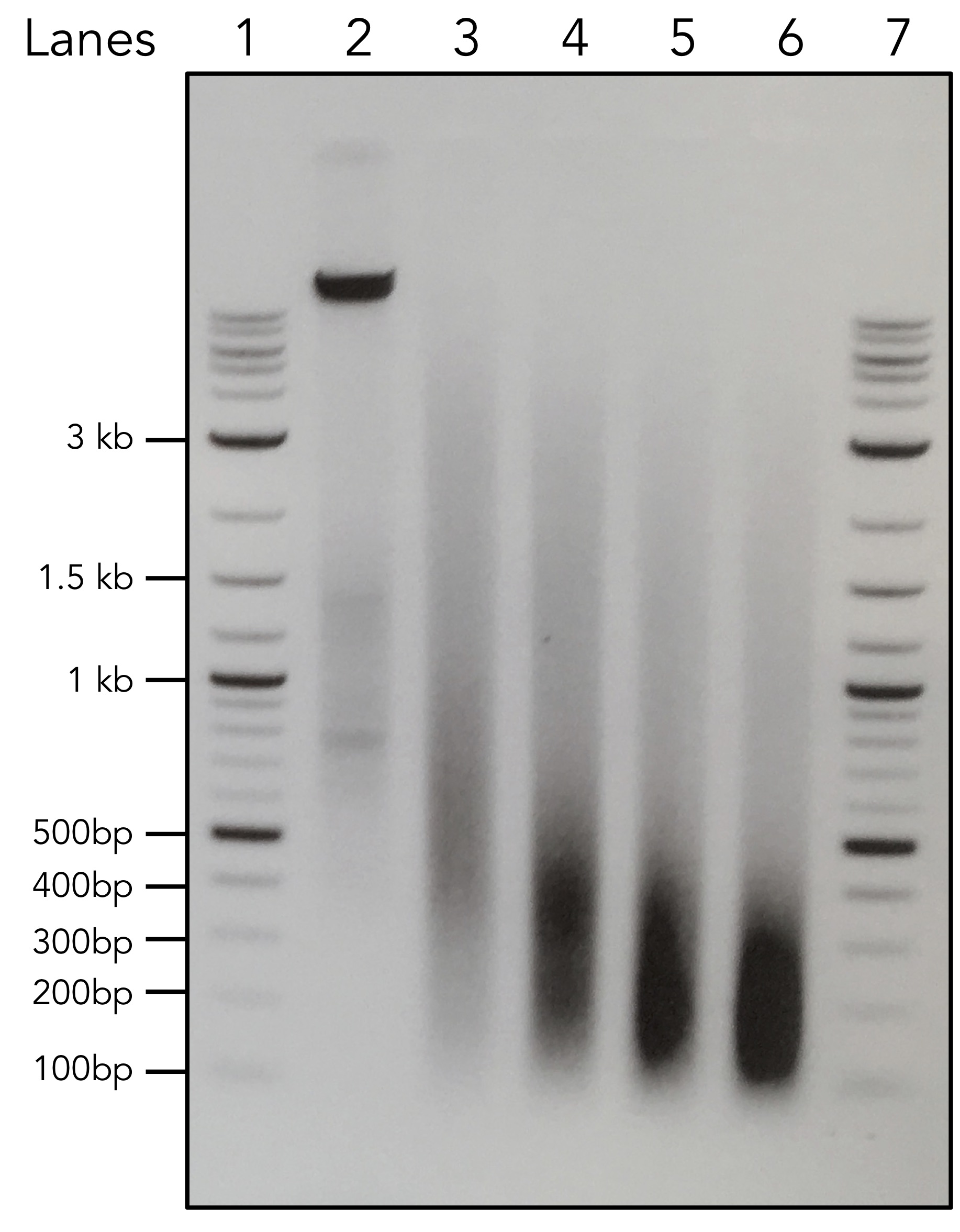

These are just four examples from mouse T cells. Different proteins behave differently. IRF4 and CTCF seems to be relatively resilient to sonication, while STAT6 and Pol II (using the famous 8WG16 monoclonal antibody) gradually disappear with increasing amount of sonication time. Histones are generally stable and not really affected by sonication (not shown here). This could be a reason why histone ChIP-seq is relatively easy, but transcription factor (TF) ChIP-seq is so difficult. One solution is to reduce the sonication time to as short as possible. Some people may say to aim for 100 - 500 bp or even 100 - 300 bp. However, that recommendation is for histone ChIP-seq. For TF ChIP-seq, I would rather have larger fragments. Look at an example shown below. Equal amount of DNA after a sonication time course was loaded on 1% agarose gel. Lanes 1 and 7 are NEB 2-Log DNA ladder, and lane 2 is un-sonicated chromatin. Lanes 3 - 6 are with increasing amount of sonication time.

So, which sonication condition do you choose for your TF ChIP-seq experiments? Unless you have tested before and know your protein epitope is stable over sonication, I would choose conditions in lane 3 to start with the experiments. It is all about finding the balance between shearing DNA and at the same time maintain protein integrity. It is not a very pleasant procedure.

Okay, finally, let’s talk about CUT&RUN: original article by Skene and Henikoff, 2017, and the detailed protocol by Skene et al., 2018. First, I divide ChIP-seq into two main parts (actually three if you count sequencing): the ChIP part and the library prepration part. There are quite a few kits developed by different companies to make library preparation easier and more sensitive. The recent awesome method variations ChIPmentation (Schmidl et al., 2015) and TAF-ChIP (Akhtar et al., 2018) cleverly utilise the transposase Tn5 to make the whole library preparation even easier than any commercial kits. However, all those improvements in the past ten years are done for the library preparation part. The ChIP part of the procedures have almost remained unchanged. This is where CUT&RUN kicks in.

The idea of CUT&RUN is not completely new. It was inspired by a publication in Molecular Cell in 2004 from Ulrich K. Laemmli’s lab (Schmid et al., 2004). Yes, from THE Laemmli, who refined SDS-PAGE and published the second most cited paper of all time :-). In their Molecular Cell paper, Schmid et al. introduced two methods to profile chromatin-associated proteins: ChIC (chromatin immunocleavage) and ChEC (chromatin endogenous cleavage). CUT&RUN is based on the idea of ChIC, and I’m not going to talk about ChEC here, and it has been adapted for sequencing (ChEC-seq). Since the publication of ChIC in 2004, the paper has been only cited 73 times according to Google Scholar at this time of writing. The method does not seem to be widely used. However, the idea of ChIC is so simple and so brilliant. In short, you do the following:

- Prepare nuclei or permeabilise cells.

- Add antibody for the protein of interest.

- Add Protein A and MNase fusion protein (pA-MN), and protein A will bind to the antibody (IgG) and bring MNase to where the protein of interset is located. So, this is the clever bit: MNase is extremely Ca2+ dependent. As long as there is no Ca2+ in the buffer, MNase will not cut DNA at this stage.

- Wash off unbound pA-MN.

- Add Ca2+ to activate MNase, and it will cut the DNA around where the protein of interest is bound.

- Collect the small DNA fragment for the analysis (Southern blot in the original publication).

That’s it! I’m going to say it again: the idea of ChIC is simply brilliant! Last year, Steven Henikoff’s lab did the community a favour and adapted this method for sequencing, and they called it CUT&RUN (Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease) (Skene and Henikoff, 2017). The obvious advantages of CUT&RUN over ChIP-seq are:

- Crosslinking free.

- Sonication free, yeah!!!

- No need for immunoprecipitation (IP), which is lossy.

- Since you do not need to do IP, theoretically, it should work with low-input cells. Indeed, it can do as few as 100 cells, or evern single cells (uliCUT&RUN by Hainer et al., 2018).

- Higher resolution (enzyme cutting always gives better resolution than sonication).

- Quick and simple (no overnight IP and reverse-crosslinking).

Very often, when a new ChIP-seq method variation comes out, it is just tested with proteins in yeasts or with histone modifications and CTCF in mammalian cells. They are informative, but you have to admit: they are relatively easy to do. What makes me feel positive about CUT&RUN is that other transcription factors (apart from CTCF), such as MYC and MAX, are shown to be working with the method.

Now, all I need to do is to establish my own lab, try it and get it to work. I am sure it will be a lot of fun :-)

Update: New methods build upon the idea of CUT&RUN , where the MNase was replaced by the transposase Tn5, were developed in 2019. These methods offer an even quicker and simpler way of profiling protein-DNA interactions in low-input and single cell level. These methods inlcude:

- CUT&TAG from Steve Henikoff’s lab.

- ACT-seq from Keji Zhao’s lab.

- CoBATCH and itChIP-seq from Aibin He’s lab.

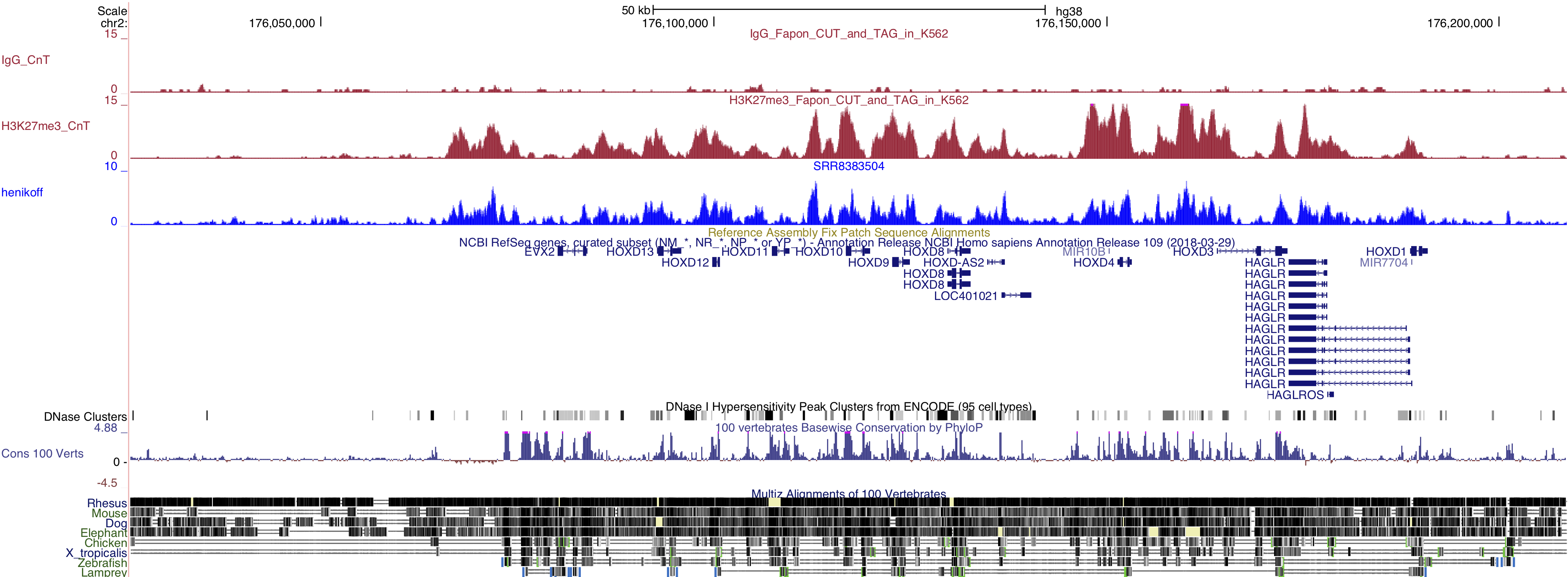

I have personally tried the CUT&TAG method, because it has a very detailed protocol on protocols.io. Dr. Steve Henikoff is also actively answering questions on the website. The method worked pretty well in my hand (at least for H3K27me3 for now). Here is a screenshot of our data: H3K27me3 in K562 cells around HOXD cluster.